Or: How These Unforgettable Films Escaped The ‘Marvel Crowd’ – A four-part series on some of cinema’s more important but lesser known movies

By Cinephile Julian Boyance

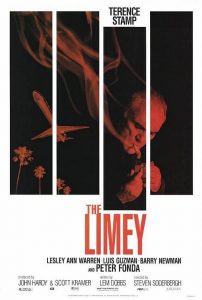

The Limey (1999, dir: Steven Soderbergh)

This is what every anti-hero film hero should be. Mean. Surly. A real son-of-a-bitch. Despite the mayhem and destruction of our protagonist Wilson, we continue to root for him. Payback (1999), similar in release date and lead, is a solid film yet does not contain such character study penetration. Each are Point Blank (1967) influenced (figuratively in this one).

Even though anti-heroes are on the fringes of society and often in contrast to our own ethics, morals, and values; the character should be compelling enough to be absorbed by their voyage. Terence Stamp owns the role as he fights through all obstacles, at all costs, to make sure protected, hipster L.A. record producer Terry Valentine (Peter Fonda) pays for his daughter’s death. Whether he is guilty or not as Wilson assumes and deduces that he is, is inconsequential. Because Wilson is coming.

Skilled DP Ed Lachman, A.S.C. and Soderbergh make a wonderful team guiding the revenge film. One built on a complex but rewarding non-linear structure which crafts this hazy memory as sensation. The Los Angeles setting is inhabited by just the right types and actors (vets Lesley Warren and Luis Guzman) to help guide Wilson’s Stateside mission of retribution.

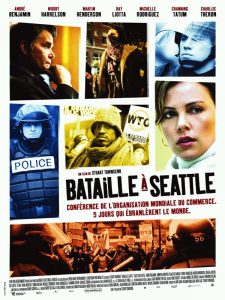

Battle in Seattle (2008, dir: Stuart Townsend)

A left-leaning film any liberal would love, Battle in Seattle speaks to the core of American values, ideology and culture enough to resonate with any viewer regardless of political/class affiliation.

Few contemporary films express the 1960s/70s militancy and political tension in America properly, yet this film succeeds in giving a feel of what marches and protests must have been like during those times. The battlefield involves contrasting entities, running the gamut of liberal, conservative and moderates, all within varying elements played under the pretense of real-life 1997 WTO events. The external and internal forces that spin the film’s shifting perspective only ups the ante for those caught in the power struggle. A wonderful mosaic, the precise casting choices in Battle in Seattle work to anchor the fact-fiction interplay, with real-life events captured in docudrama style, which works to structure BIS as distinct cinema.

Who knew the man able to transport Anne Rice’s Lestat to life as an actor would make such a remarkable directorial debut. And when will that elusive second film come forth?

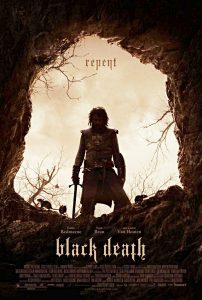

Black Death (2010, dir: Christopher Smith)

Fantastical, spiritual, lyrical, and supernatural all-in-one, this ominous tale of Medieval England circa 1348 is full of horror, death, and pestilence (as the title suggests) – not necessarily for the faint of heart.

Talented director Chris Smith (one to watch since Triangle (1998)) elevates the film’s dense, straightforward story of a lost love gone horribly wrong. Despite the film’s lower budgeted roots, few films have photographed this time period and legendary pandemic with such immediacy. The film is one exemplar where I’ve said, “Okay, the digital camera really elevates the content here.”

Blessed with the ever stalwart Sean Bean and a capable UK cast, the film has the serendipitous fortune in Eddie Redmayne being cast not long before his Oscar win, though the film is probably little known even by his fans.

Mystery, Drama, Horror? Which is it? … All of the above.

The beauty of the film is that it’s genre is obscure. The fanatical religious heresy hunt and pagan exploration propelling the film is sincerely frightening [in tone]. And, our shy and reserved monk hero’s religious allegiances continue to be grippingly conflicted throughout.

Just as spooky, better developed and larger-in-scope than the much talked about The Witch (2015), the bubonic plague disease and its palpable presence intensifies and fortifies the themes profundity of said explorations.

Kudos sent to Magnet Releasing continuing to be at the fore of unique and challenging films.

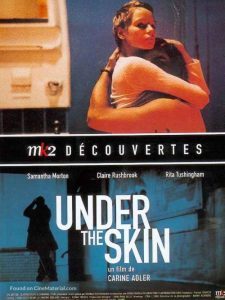

Under The Skin (1997, dir: Carine Adler)

When the recent Scarlet Johansson vehicle, similarly UK-based and titled, esoteric masterpiece was released (2014) I was disappointed. Unfortunately, the title of the film is more connected to the recent release rather than the perfectly captured, “arthouse/indie 90s” ethos that, despite being critically acclaimed in the UK, was barely seen. The original introduced a talented actress in the low-key style: Samantha Morton (Iris).

I’ve long had an affinity for the working-class, “kitchen sink realism” resurgence seen in UK films post-Thatcher. The work of Mike Leigh like High Hopes (1988) is certainly at its core.

England has nurtured some interesting cinematic voices where realistic stories and a new breed of visual stylist have shifted the grounded politically bent work laid by Ken Loach and Tony Richardson. Since the 90s, fresh stories and theatre and/or commercially trained proficient talent in front of and behind the camera (Julien Temple, Danny Boyle, Jonathan Glazer, Shane Meadows, Steve McQueen, etc.) have raised the UK profile.

This feminist tale of loss, grief, and “finding one’s way” may be a bit edgy for some, but for people who have experienced family/parental mourning, the risky and puzzling behaviors are what energizes the protagonist’s alluring, singular journey of finding self.

If you dug UK release, Shame (2011), you should appreciate the themes and tone of Under the Skin.

If you are wondering why the director’s name does not look familiar, it may be like other similar enigmatic occurrences, a filmmaker with a vibrant debut then has no second feature or few works thereafter. Gillo Pontecorvo and Benjamin Ross amongst a few others come to mind. Strange and disheartening.

FIPRESCI International Critics’ Award winner at the 1997 Toronto Film Festival, in UK film circles, Under the Skin is a much remembered and respected work.

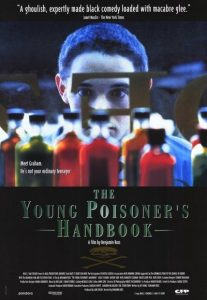

Young Poisoner’s Handbook (1995, dir: Benjamin Ross)

No doubt one of the most indelible films I have ever beared witness. Like the recent The Lobster (2015), the imagery and storyline were unshakeable for years afterward. Part of my fascination was the difficulty of attaining a DVD or copy since the DVD release took almost ten years after the theatrical release.

An unbelievably true-crime tale of a bug-eyed, cherub teen, who, if judged by external appearance seemed to be the harmless boy next door type. As been often said, it is the quiet types one has to be on the look-out for. And this film proves that point judiciously. With a youthful face like Anthony Perkins as Norman Bates, the innocuous façade belies a devious and sinister interior bubbling to the surface.

As the film’s title suggest, the film explores and exposes the sullen soul of a teen corrupting toward criminal and moral abyss with clinical tact. Ghoulish and macabre humor are naturally instilled in the matter-of-fact manner our ambitious young man Graham approaches his mischief.

When the film finally became available on DVD, my re-evaluation upheld what a devastating and creepy account of the boy next door turned deceptive murderer. 1960s suburban London authenticity conveys the impression that the film was actually shot back then. Meanwhile, flourishes of lively camerawork stimulates the black humor. Personal fave Heavenly Creatures (1994) is comparable.

With a nod to Clockwork Orange (1971), rehabilitation and recidivism of the criminal mind remains as hauntingly unforgettable as ever.

A philosopher with a camera, a Mont Blanc, and a laptop. Taught by the likes of Godard, Eisenstein, Welles, Scorsese and Lee ~

Julian Boyance is an filmmaker/blogger/film instructor hailing from Metro Detroit area whose cinematic journey traverses both academia, production, and beyond.

Facebook administrator for the Nicolas Winding Refn Appreciation Society fan page, his social media footprint can be found here: Twitter/Instagram: @godardfan Youtube: Godardfan Tumblr: Godardfanforever