Born and raised in New York City, Luisa Colón began her career as a journalist in the late 90s; her work has appeared in numerous print and online publications such as New York, Latina, USA Today, and The New York Times.

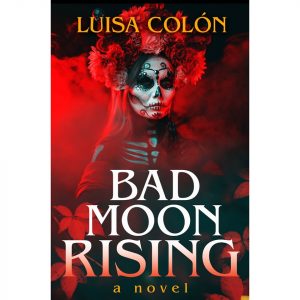

Luisa also made a brief but successful foray into acting, starring in the award-winning 2006 indie film Day Night Day Night as well as the titular role in Alejandro González Iñárritu’s 2007 short film Anna. And then, as rapidly as Colón had hit the film scene, she moved on to other endeavors: becoming a mom, creating artwork (two of her murals are currently on display at the World Trade Center), and writing her first novel, BAD MOON RISING.

File under Horror.

Anthony Brancaleone: So, you’re currently living in Brooklyn; what is your definition of the city?

Luisa Colón: Brooklyn is New York City’s largest borough and at this point in my life, Brooklyn = NYC. So much is in Brooklyn, and for the things that aren’t, standing across from the Manhattan skyline in Domino Park, Bay Ridge, Red Hook, DUMBO, the Brooklyn Promenade, or other spots will give outsiders a perspective and a scale—both emotional and physical—of NYC that they’d never get to experience from being in the city itself.

AB: How has Brooklyn changed through the years?

Luisa Colón: I grew up in Manhattan and my first apartment, the first place I ever lived by myself, was in Brooklyn, which was more affordable and less desirable at the time. I moved there when I was 22 and it was a studio in Park Slope that cost $550 a month. In high school, I had friends who lived in Park Slope and it was still a little scrappy back then. We would rent videos and eat at Smiling Pizza, which we called Smiley’s. When I moved there, Smiley’s was still there, but a cute little trendy diner was opening up on the corner across the street from my apartment. Then the changes accelerated, like the area was transforming in fast motion. Goodbye bakery, goodbye sewing shop, goodbye mainstays. Smiley’s prevails, though. People who visit New York City should walk around as much as possible, and not be afraid to explore. Walk. Eat. Take public transportation. And look at Manhattan from across the river.

AB: What was life for you growing up in Manhattan?

Luisa Colón: I loved growing up in Manhattan. It feels like everything is possible until you realize it’s a comfort zone just like any place can be a comfort zone and that you need to get out of it in order to grow. I loved hot dogs from street vendors when I was growing up. I’m so finicky now I probably wouldn’t get one. There was a restaurant in the lower level of Bloomingdales called Forty Carrots and they made my favorite frozen yogurt in the world. It was sour. I never tasted yogurt like it until Pinkberry came along and I was ecstatic—the sour yogurt was back!! The only time I ever cut out of school was to get Peter O’Toole to autograph his book for me at Brentano’s. For my birthday one year, I got to go to the Four Seasons. There was a sort of pool of water in the middle of the restaurant, and Shelley Winters said in her autobiography that Laurence Olivier floated flirty notes to her across that pool. There’s so much history in New York. Ghosts are everywhere. They’re good company.

AB: So, did your acting opportunity present itself in Manhattan or Brooklyn?

Luisa Colón: This is very NYC. I was a nanny and pushing a stroller on the boardwalk in Coney Island and I saw a flyer for an open casting call, for a movie. I obsessively love movies, and I also went to the High School of Performing Arts for drama, so I was like … hey, looks cool! The two directors I was privileged to work with, Julia Loktev and Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu, accepted me as a film lover who could follow directions and take part in a creative experience. Like “We are humans, looking for another dedicated human who would like to practice their craft.” They spoke in a language I could understand. I love hard, challenging work. I loved the process of filmmaking. I thought, “Sure, I’d do this again.” Then I set foot in LA and entered a netherworld, and came running out screaming with my hair on fire.

AB: I’m always curious to know what movies New Yorkers feel best represent the city?

Luisa Colón: A lot of Woody Allen’s movies really captured a very specific subset of New York, perfectly. But it was very specific. There are moments in movies where you catch a glimpse of authentic New York because they were filmed on location, like a handful of scenes in West Side Story or Love With a Proper Stranger. Various independent movies; there’s a 1997 film called All Over Me that really captured Hell’s Kitchen. Living in Oblivion, which is from 1995. I don’t know why it’s independent movies that capture NYC so well unless it’s just that they’re not looking at the city through reams and reams of money, so you actually see something authentic. I think Day Night Day Night really captures NYC because we shot it guerilla-style on the street with people around who didn’t realize they were being filmed. I’m not objective with that one, but there is an authenticity that’s pretty unmatched. I can’t think of another movie like it.

AB: You played a polite, would-be suicide bomber in Day Night Day Night – how did you prepare for the role and what lessons did you take away from the experience?

Luisa Colón: Julia and I immersed ourselves in the process, she as the filmmaker, me as the actor, and it was awesome. We were careful about every detail—it was like we were sewing something and never missed a stitch. For me, the approach was really clear. I couldn’t relate to that character’s situation, but I could transpose my own situation onto it and it worked out great. Young girl entering an entirely new situation, eager to please, under a tremendous amount of pressure, pretending to be something she wasn’t. That was all me, except the young part. My character was in her teens and I was almost thirty. I do the same type of immersion in my writing.

“Ghosts are everywhere. They’re good company.” ~ Luisa Colón

AB: How did you make the leap from starring in a film to writing a novel?

LC: I think the leap was more into starring in a movie, because I’ve been writing stories since I was a kid, and became a freelance writer for magazines first. But I love movies. Growing up, I worked for years in a video store in Manhattan, with all the nerdiness that such a position entails: watching films over and over, reading about them, and writing about movies (largely for myself). When the opportunity to star in DAY NIGHT DAY NIGHT came up, I told Julia that I was fascinated by the process of filmmaking but not too interested in the idea of being an actress, and she was fine with that. And it worked out. Then I became a mom, and then I went back to freelance writing, which I had been doing before DAY NIGHT DAY NIGHT—articles about anything and everything—and illustration on the side. AB: So, you just decided to write a book?

LC: I was enjoying my writing so much, even the silly stuff I was doing for very little money. I just love to write, even when I’m producing content that can be totally meaningless. And I just felt like, I want to take my writing to the next level. I was inspired by my Puerto Rican great aunts, who practiced witchcraft. So I put my freelance stuff on hold and buckled down and wrote my book. I stayed up at night. I’d put my kids to bed and set my alarm for 10PM—because I invariably fell asleep—wake up, and begin writing, eating chocolate, drinking chocolate, basically inhaling chocolate to keep myself awake. I would dip chocolate bars in hot milk to create the ultimate hot cocoa. I feel like my novel was built on a foundation of chocolate.

AB: Look at how you casually dropped ‘witchcraft’ and moved on. Is this practice a strong family trait?

LC: My father’s aunts in Puerto Rico were practicing witches, but they passed away before I was born. I feel like there is some of them in me—the determination and willfulness to get my way and make things right even though it means thinking way, way outside the box. As an adult, I was trying to figure out how to deal with some obnoxious neighbors, and a Latinx woman reached out to me on an email group and suggested putting a broom on the inside of my front door, upside down, and saying “Go away” to it. My neighbors didn’t go away, but the situation got better, and I felt better about it. People would come over and go “What’s with the upside-down broom?” And I’d say “It’s Puerto Rican witchcraft.” Nothing stops people dead in their tracks quite like telling them you like to throw a little Puerto Rican witchcraft around.

AB: What are some basic defenses we can use against hexes and or spells? And, respectfully, if one were to upset a witch is there way to make amends before or during her wrath?

I’m all about talking things through. I imagine if I incurred a witch’s wrath, I would have to talk it out, do some good asking and listening and mirroring. Really pull out the dialectical behavioral therapy tools: GIVE, FAST, and DEAR MAN. You’ll have to look those up, those are DBT interpersonal effectiveness skills. Listen, be gentle, maintain self-respect, and some negotiating techniques, I guess. “I would like for you to remove your hex on me, here is why and how it might benefit you.” If Billy Halleck had tried to make actual amends in Stephen King’s THINNER, things would have gone a lot differently for him. Accountability is important.

AB: And, what about chocolate – the “foundation” of your novel?

LC: I’d just go to the supermarket and get milk chocolate bars—Lindt. Fancy chocolate leaves me cold. When I was little I used to eat a type of milk chocolate called Snow White chocolate. It was a chocolate bar, and on the wrapper was a painting of Snow White and the Seven Dwarves. Where I grew up, in the Yorkville area of upper Manhattan, there was a chocolate shop called the Marzipan. Nothing has ever measured up to Snow White chocolate and the Marzipan.

AB: Your book Bad Moon Rising is a work of Horror. What is it about the genre that appeals to you?

LC: I have loved horror since I was twelve years old and saw Psycho. It’s something I’ve written about and talked about a lot, because people are always curious—why horror? I trace it back to seeing Psycho for the first time. When Tony Perkins makes his first appearance, he’s coming down a long, steep staircase at night, down a hill in the pouring rain, holding an umbrella that he never opens. From that moment on, I knew I wasn’t alone in the world, that there was an upside-down where I belonged, where it was okay to be me, okay to create what I wanted to create. That’s a very comforting, liberating feeling.

“Nothing stops people dead in their tracks quite like telling them you like to throw a little Puerto Rican witchcraft around.”

AB: Why do we dislike terror on the world stage, atrocities, violence, but then feel compelled to work in or entertain ourselves with horror?

LC: I guess for some, it’s simply a release and a safe way for them to be … what, thrilled, scared, sadistic? An adrenaline rush? Dopamine release? “Better them than me?” But my favorite kind of horror is truth, when the filmmaker really has something on their mind and they’re trying to express it. Hitchcock had a lot to say—creatively, technically, and definitely on an emotional and pathological level. It’s all there.

AB. Have you had many scary experiences?

LC: I spoke at an event last fall where we had to tell real-life, fun scary stories. My go-to is how once, as a teenager, I was in what I thought was an empty bathroom in a shambling building in midtown Manhattan, and I couldn’t get into a bathroom stall that appeared empty. So I put my eye up against a gap in the door to see what was going on, and there was a crazed eyeball looking back at me. Someone squatting in the bathroom maybe?

AB: That’s creepy.

LC: One of the least-scary experiences I ever had was, as an adult, someone else’s kid tried to prank me by leading me out into the rural woods to “show me something” and then ran off with the flashlight, leaving me in the dark. I could not have cared less. I was like Dude, I’m a New Yorker and a mom. I give zero fucks about being in the woods at night. Bring it—this is what moonlight is for.

AB: How much of Bad Moon Rising is autobiographical then?

LC: Almost everything that happens in Bad Moon Rising is autobiographical. I can point to about 90-95% of the book and explain how it happened to me. Usually not literally, but there is a true, organic origin to most of it. I explain it this way: let’s say something happened to me that made me feel as if I’d been stabbed in the gut. When I write about it, someone actually gets stabbed in the gut. So that’s how I mean it’s autobiographical. And that’s one of the ways horror is so liberating, because you get to depict how you actually feel or felt, as a complicated person in an inexplicable world, without the constraints of having to be realistic.

AB: Are you writing regularly?

LC: I find time for writing any way and anywhere that I can, and that is how I access my craft, period. I make time, I find moments. As a mom, and someone who is constantly hustling for a living as a writer, editor, and artist, that’s the only way I can do it.

AB: I usually work from a laptop in my home; moving from office to kitchen table to sofa, drinking Café Bustelo (which, I first had in El Barrio in the early 90s.)

LC: Thank you for sharing that, I like to know how other people work. Coffee has replaced chocolate. I drink too much coffee. I have to. However, I do add a ton of chocolate to my coffee. So I guess it’s been a seamless transition. I’ll write from anywhere, including work, cafes, and on the subway, but my most preferred writing spot is on my couch with coffee, my two cats, and my pet bunny. I will also sit on the floor or on my bed. I need my laptop but in a pinch, I have written on my phone while on the train or waiting in line for something.

AB: Who are you reading?

LC: Lois Duncan was a huge influence on me, and still is. There is so much pain and truth in her books and they’re also scary as fuck. I just finished Paul Tremblay’s Headful of Ghosts and it was amazing.

AB: And, music?

LC: I’m still obsessing over Morrissey and the Smiths. It’s been years now and that’s still going on. Not as long as you would think—I got into Morrissey as an adult. I also draw a comic called “The Mizerable Misadventures of Morrissey & I” that’s about me and Morrissey as an average, bickering couple. There’s other stuff I like, of course, which is more a la carte.

AB: And, apart from Psycho, what other monsters or scenarios have you seen in film that shook you?

LC: The situations on the original Twilight Zone television series make for some really, really scary monsters. In “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet,” William Shatner is an airplane passenger who keeps seeing a gremlin on the wing of the plane, fucking shit up. But no one believes him because he has a history of mental health issues. The gremlin is scary, but not as scary as that predicament, of being perceived and judged as mentally ill and therefore someone who is not to be taken seriously or at their word.

AB: I’ve seen that episode.

LC: John Carpenter’s The Thing is one of my favorite movies in the world, and it’s chilling. Again, the monster in its various forms is scary, but the idea of looking into a friends’ eyes and suddenly seeing no connection, no empathy, that’s definitely more frightening. When they keep going in circles in The Blair Witch Project. Being the last real person in the world in Invasion of the Body Snatchers because everyone else succumbed to one of the most natural needs in the world: sleep. I guess the common thread is not knowing people and not being known; having your emotions and needs go unrecognized because no one cares or they want to hurt you; having zero control in any situation, really, but in an interpersonal, vulnerable situation especially.

AB: You are quoted as saying your next book is “as dark as it needs to be.” – how dark does it need to be and what is your suggestion for dealing with darkness?

LC: Pretty fucking dark. I think with BAD MOON RISING I was feeling a little apologetic because when I first wrote it, a) I didn’t know I was writing horror and b) I got so much pushback from agents and publishers who said it was “too dark.” I felt self-conscious and like there was something wrong with me; I forgot the rightness of Norman Bates running down the stairs in the rain with his closed umbrella. I was being careful.

AB: What is it like trying to find a publisher?

LC: Ridiculously hard. After I finished the first draft, I started querying agents. I queried a lot of agents and kept a spreadsheet and so on, and I just got rejection after rejection. Eventually I did sign with agents, who threw up their hands after a couple of years of trying and failing to get it published. After that little divorce, I started contacting publishers myself, and this time something really clicked with me. I realized, This IS horror. The reason all these normies find it so disturbing is because it’s horror. And I need to be with my peeps, not someone who will tell me to lighten up or ask me to slap what they consider to be a happy ending onto my story. Thankfully, I connected with Kevin Lucia at Cemetery Dance Publications, and I felt like, Wow, I’m finally home. I found my people.

AB: So, now you’re free to explore the depths …

LC: In my second book, still in manuscript form, I accepted that this is my experience, my pain, and I get to write about it however the fuck I want, and that’s going to be untenable to some people. But it’s mine, I own it, and I’m going as dark as I need to in order to authentically record and express it.

AB: You are speaking to yourself 20 years in the future – what do you want your future self to know about you at this moment in life?

LC: That I still didn’t know how strong I was. Hopefully my future self will have a good knee-slapping laugh about that. Like, “Are you serious?”