We are still in rebuilding mode; internally, externally, metaphysically. So, here are three more books to help guide us to the promised land (or, at least, to February, when we focus on sex & chocolate).

Be well out there.

_________________________

Quick Wins! Using Behavior Science to Accelerate and Sustain School Improvement

Quick Wins! Using Behavior Science to Accelerate and Sustain School Improvement

By Dr. Paul Gavin and Anika Costa

While educational leaders are eager to make a difference, a common mistake is putting too many demands on faculty and staff during the initial stages of change. Perfect for educators at any level (a school district official, principal, assistant principal, dean, guidance counselor, behavior analyst, teacher, school consultant, or home school educator), Quick Wins! focuses on the impact of highly visible, low effort achievements that deliver a valued outcome for all team members.

In the second edition of the book, bestselling authors and educational consultants Dr. Paul Gavin and Anika Costa deliver a systematic approach grounded in organizational behavior science for achieving results and rapidly transforming schools, and bringing out the best in your students, faculty, staff and yourself. In this updated edition you will find:

- New and improved stories and expanded examples of Quick Wins.

- A transition from traditional S.M.A.R.T. Goals to IMPACT Goals powered by behavioral science.

- Quick Takeaways and Sustain It actions to extend the learning experience to actual improvements in schools and much more.

“People want meaningful improvement and they want to see it quickly,” the coauthors explain. “These improvements are easily identifiable, as they could have, and should have, been made long ago. A Quick Win does not have to be profound or have a long tern impact on your school. However, the best Quick Wins are long lasting and leave a profound effect on faculty and staff’s interest and ability to make long term impact changes happen. One thing is certain: A Quick Win necessitates that people agree on the need for change, act together to make the change, and learn from the change. To make such change happen, Quick Wins requires leadership.”

School leaders are critical to staff performance and student achievement. By taking Quick Wins approach and developing leadership and staff skills as described in this book, success is a matter of “when”, not “if”.

_________________________

URGENT CALLS FROM DISTANT PLACES

URGENT CALLS FROM DISTANT PLACES

Introducing emergency medicine physician DR. MARC-DAVID MUNK, whose forthcoming book URGENT CALLS FROM DISTANT PLACES: An Emergency Doctor’s Notes About Life and Death on the Frontiers of East Africa [Creemore Press | January 30, 2024] is not only a front-row seat to the harrowing realities of medical relief work in Africa; more so, it is a brutally damning appraisal of the pitiless and cruel ethical shortcomings of the modern American healthcare system.

After suffering from the all-too-familiar burnout that so many emergency medicine doctors experience, Marc joined AMREF’s (African Medical and Research Foundation) Flying Doctors to get back in touch with why he chose to practice medicine in the first place. His work there only served to highlight for him how truly broken the Western medical system is, and he returned to the US committed to refocusing on building alternative care delivery models that work. As the Chief Medical Officer for Clinics and Retail Pharmacy at CVS Health, his hire was, according to journalists at Bloomberg, “a sign that the drugstore chain is serious about providing more medical services directly to consumers.” Before that, he was the Chief Medical Officer at Iora Health, which Amazon acquired in 2023 for ~US$3.8 billion.

Marc’s story is one of burnout, reconnection with medicine’s fundamentals and a subsequent mission to revolutionize healthcare. He has appeared on ABC News, PBS Newshour, NPR and CBS News and work has been featured in Business Insider, USA Today, and Health Leaders Magazine.

About the Author

MARC-DAVID MUNK a Canadian/American and a prominent figure in healthcare, driving change in emergency medicine and healthcare management across the U.S. and internationally. His career began as an emergency medicine professor and as the medical director of Qatar’s national ambulance service. Advancing to executive roles, he served as Chief Medical Officer for elite physician groups and as the regional President for an international division of a leading American healthcare system. His medical training was completed at Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia, followed by an emergency medicine residency and an international health fellowship at the University of Pittsburgh. He also holds a Diploma in Tropical Medicine from Peru’s Gorgas Program and a master’s in healthcare management from Harvard University. Dr. Munk lives outside Boston with his wife and two children.

_________________________

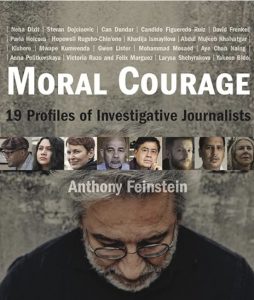

Moral Courage: 19 Profiles of Investigative Journalists

Moral Courage: 19 Profiles of Investigative Journalists

What drives these journalists to persist in their mission, undeterred by grave perils?

What drives those in other professions to willingly step into danger zones to serve as messengers, help treat the wounded or provide food, comfort and relief?

Neuropsychiatrist Anthony Feinstein, Ph.D., interviewed 19 investigative journalists who live in countries with an intolerance of a free press, from Russia, Iran, Syria, to Zimbabwe. He found one common denominator in each of them that compels them to tell an inconvenient truth despite the risk of torture, vicious harassment, death threats, imprisonment, and mock execution – MORAL COURAGE — the title of his new book exploring this attribute. Our thanks to the author for allowing us to share the following excerpt:

MORAL COURAGE

By Anthony Feinstein

India

NEHA DIXIT

To understand India’s slippery descent, one should read the reportage of Neha Dixit, a thirty-seven-year-old New Delhi-based freelance journalist. Her exposure of the deep strains of racism and misogyny that currently course through Indian society, nurtured by a resurgent militant nationalism that stokes intolerance for political gain, has made life hazardous for her. She could not have anticipated the harassment that over time has engulfed her career, but even if she had, I doubt it would have deflected her from her course. Not with her finely set moral compass.

Dixit grew up in an upper-middle-class family in Lucknow, in the state of Uttar Pradesh, approximately 500 kilometers from New Delhi. Her father worked in a government bank and her mother was a teacher. Education was prized in her family, and although young Neha excelled at school with a 90 percent average, she remembers being pressured to match her brother, whose grades were in the mid 90s. An independent, free spirit, which would become evident in her work as a journalist, was present at an early age. Unbeknownst to her parents, and bucking rigid gender-based conventions in Lucknow, she rode a scooter. Neighbors, aghast at her behavior, informed her parents of this and moreover let them know she rode fast and honked at boys.

Looking beyond these adolescent peccadillos, however, were more serious disagreements with her parents. They opposed her desire to become a journalist. Her father was influenced by his father, who saw the profession as little more than stenography, a clerical position, not suited for a woman. Studying in New Delhi was also frowned upon, the city viewed as a gateway to drinking, smoking, and falling pregnant. Rather stay put, they urged her, and study medicine.

Dixit would have none of it. She did not want to be a doctor. Rote learning was not for her. She liked writing and poetry and already, by thirteen years of age, had had some of her work published in a community paper. She was determined to go her own way, to escape what she saw as the “crystalized choice of her parents.”

“You have aged me by ten years.” This rebuke from Dixit’s father as she set about her studies in New Delhi came to haunt her. Within six years of her leaving home, he was dead. While the cause of death was complications arising from diabetes, Dixit has never fully shaken off the guilt she felt at his passing.

Misplaced guilt aside, university proved liberating. As Dixit recalls, a liberal milieu at Miranda House, a college for women at the University of Delhi, afforded her a “chance to understand the world.” Her newfound freedoms away from the rigid conformities of life in Lucknow offered small, unexpected pleasures, as well. She could wear her hair loose without fear of being judged amoral and being stalked. To her amazement, she could even go to a midnight movie on her own. Shedding the constraints of a controlling patriarchy allowed her to see that her relationship with her father was indicative of what women in India endured. Insights like this steered her toward women’s rights issues. It was part of her awakening as a woman in a tolerant university environment, and it set her career course.

By the time she was twenty-two years of age, Dixit had completed an undergraduate degree majoring in English and a two-year master’s degree in journalism, the latter from AJK Mass Communication Centre, a constituent institute of the Jamia Millia Islamia, also in New Delhi. To forestall family pressure to return home and settle into the conformity of an arranged marriage, she never told her parents that her studies were complete or that she had subsequently taken a stopgap position for a tech company writing content.

A month later, she landed her first journalism position writing for Tehelka, a news magazine known for investigative journalism and sting operations.

Her first cover story reported on human trafficking in India and the sexual exploitation that accompanied it. Women were being sold off as brides. Her research took her into red light districts, which appalled her father. He beseeched her not to share this story with family members. Good girls stayed away from such areas, he admonished her.

Another of her stories exposed the honor killing of women. Diktats from courts in northern India held that women could not choose their partners. Those who did ran the risk of being killed. Moreover, there was no accountability for the extrajudicial killings.

Stories like these infuriated conservative, reactionary elements within Indian society. Social media had yet to take off, but blogs were popular and one way to threaten a journalist. Dixit was warned that she would be beaten “black and blue.” She recalls being chased away from more remote mining areas where she had gone to collect firsthand accounts of gender-based violence. The pressures and dangers that came her way were endured alone. No support was offered. The responses from management at Tehelka were either to compliment her on her bravery or to normalize the experience as just one of those things that came with this type of work.

Looking back on this nascent period in her career, Dixit recalls that her toughest challenge was not the incipient violence that dogged her steps, but rather the sexual harassment she had to endure from her editor. At the time, there was simply no recourse for her to deal with it. This was not only a Tehelka-related problem, she realized, but a systemic issue faced by women journalists elsewhere. And unhappy as she was about it, she could not simply up and leave her hard-won position, because, as she saw it, doing so would prove her family right and all the pressures for her to return home and be married off would crank up again. “It was very difficult not having any moral support,” she divulged. “I was quite alone and very young.”

Despite the pressures that came with her work, Dixit liked what she was doing. She pushed back against the constant urgings of her family to pursue film journalism, a safer and less controversial career path than the one she had set her sights on. Bolstering her resolve was the impact her stories were having, like her exposé of child labor practices that led to the rescue of 250 children. An outcome like this validated her work and kept her motivated to pursue socially relevant, albeit emotionally fraught, issues.

After three years at Tehelka, Dixit wanted to try television journalism and took a position on the investigative desk at India Today. Her switch to TV pleased her family. Not only could they now see her on the air, but they could also use her screen presence to attract potential suitors for an arranged marriage by telling them to “check her out.” What they would have seen during Dixit’s thirty minutes on the air was a journalist committed to exposing morally egregious behavior perpetrated by people with power. Her topics ranged from honor killings to the use of child soldiers by Maoist insurgents (fighting the Indian government in remote rural areas for better land rights and jobs), to the dubious ethical practices of Big Pharma. In relation to the latter, she revealed how pharmaceutical companies were undertaking clinical trials on poor, abandoned mentally ill patients in government hospitals in the state of Madhya Pradesh. Exploiting the most vulnerable of individuals made a mockery of the sacrosanct medical process of informed consent, and patients were paying with their lives and side effects. Her story galvanised the Indian Medical Association into taking action. All clinical trials throughout India were halted for two and a half years to clean shop.

Featured image by George Milton