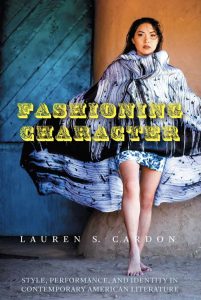

Q&A with Lauren Cardon, author of Fashioning Character: Style, Performance, and Identity in Contemporary American Literature

“When I read a description of clothing, I pay attention,” says Lauren S. Cardon. Her book Fashioning Character: Style, Performance, and Identity in Contemporary American Literature will have readers doing the same—and then taking their observations to myriad levels, as Cardon does with everything from film and television to magazine covers and her morning commute.

“It was one thing to read about Scarlett O’Hara turning curtains into a dress, and another to see Vivian Leigh flitting into a room in the transformed velvet portieres,” muses Cardon about the origin of her interest in the meaning of fashion. An Associate Professor of English at the University of Alabama and the author of Fashion and Fiction: Self-Transformation in Twentieth-Century American Literature, Cardon sees a profound connection between clothing and the journey of self-discovery and transformation.

Here she talks about first making that connection, pandemic-era fashion, and the ladies of And Just Like That…

Author Lauren S. Cardon

“I was really struck by the positives and negatives of the fashion industry”

How did you first become interested in the connection between fashion and broader societal, cultural, and literary constructs?

My interest in the connections between fashion and literature came about very organically, through seeing film adaptations of literary works. Seeing Audrey Hepburn in the opening scene of Breakfast at Tiffany’s is a different experience than reading about her “slim black dress” and “pearl choker” in the novel. It’s not that I like the films better, but they helped me visualize why these details in the novel matter. The adaptation to a visual medium teases out some of the details that I might have skimmed or overlooked entirely in a book. I remember when Baz Luhrmann was adapting The Great Gatsby, his wife Catherine Martin, who did the costume design, talked in an interview about how Tom Buchanan wore his polo outfit to dinner rather than changing into dress clothes, and she elaborated on why that was important. These types of moments in film retrained my reading of texts and even other social situations, like what politicians wear for a debate or big speech.

In your book FASHIONING CHARACTER, you write about how fashion reflects—often in very nuanced ways—the current social, economic, and cultural milieu. How do you see American fashion now, as we approach year two of life during the pandemic?

I see a much bigger focus on leisure and comfort. The pandemic has placed new logistical demands on people (juggling childcare or homeschooling and cooking more at home, just to name a few) while also allowing for more telecommuting. More people have been working in their pajamas or yoga pants, and it’s hard to do that for months and go back to any clothing that feels unnecessarily uncomfortable. I recall a friend asking on her social media page, “Where can I find professional-looking pants that feel like yoga pants?” Some people may be starved for getting all dolled up, but for the most part I’m seeing more leggings or loose, wide-legged trousers, cozy knitwear, slouchy boots, flowy skirts––items that say “comfort chic.”

You write that fashion has the potential for “aesthetic pleasure and self-expression—even self-discovery.” What do you think that means now as transgender issues increasingly come to the forefront?

Clothing can be critical in constructing gender identity for both transgender and cisgender people. Even among cisgender women, for example, we may gravitate toward more feminine or masculine or androgynous clothing. It’s the same for transgender people, only, clothing might carry an additional significance in gender construction because it might help facilitate that initial exploration of gender identity. I think it’s important to point out that public perceptions of transgender identity tend to reflect the experiences of celebrities like Chaz Bono or Caitlyn Jenner or Laverne Cox––whose gender presentations are very masculine or very feminine. Caitlyn Jenner, for example, whom many knew as a very masculine male athlete, had a kind of big reveal moment with Hollywood hair and a satin bodice on the cover of Vanity Fair. But for some transpeople, it’s not a matter of going from a masculine to a feminine appearance or vice versa, but finding something in-between. Not all trans people have gender confirmation surgery, not all transpeople take hormones, and not all transpeople exclusively dress in male or female clothing but settle into a more gender-fluid presentation.

You lived in New York for two years. How did that affect your perspective about fashion?

I definitely think the two years I lived in Brooklyn brought out a more analytical approach to fashion. I always noticed, when riding the L train, how many women were dressed in a similar style––typically a cool blouse or t-shirt, a blazer, jeans, some slouchy boots, a hat (maybe in a newsboy style), and a large purse––sometimes a scarf or piece of statement jewelry. The look seemed effortless, and somehow reflected the general feel of my neighborhood at the time. And it made me notice how different neighborhoods of New York had different looks. I found that fascinating. Were people really signaling their neighborhoods and affiliations through their fashion choices?

As you noted in FASHIONING CHARACTER, fashion played a notable role in the Sex and the City series. What do you think is the significance of the evolving styles in And Just Like That?

I really like that we’re going to see another series about women in their 50s (or older) that focuses on their lives. Moreover, I love that it’s a show in which the central women, all in their 50s, are positioned as fashion icons. I don’t remember another show like that since The Golden Girls. We love to poke fun at the clothes on The Golden Girls now, but really, they were very chic at the time!

As I mention in Fashioning Character, one of the big fashion takeaways from Sex and the City was its emphasis on personal style: Carrie, Charlotte, Miranda, and Samantha all wore fashionable clothing, but they looked completely different and wore clothes that reflected their personalities and lifestyles. And while I don’t like age-specific fashion rules (like you can’t wear a mini-skirt after a certain age), I do think that stylish women update their fashions as they age––our bodies and lives change, and it makes sense that our clothes do as well. So I’m interested to see what Carrie, Charlotte, and Miranda are wearing now, in their mid-50s. One thing I notice from the trailer is that And Just Like That will be a little more representational than Sex and the City. The showrunners aren’t just casting a single BIPOC side character, but incorporating a host of new characters who represent different cultures and gender identities. More representation for this series is not only necessary and responsible, given the series’ popularity, but personally I hope will translate into more diverse examples of personal style. I’d like to see fewer people running out to buy Manolo Blahniks because of the show, and more people looking at a range of different characters, cultures, gender identities, and other expressions of selfhood, and thinking, “That style––that looks like me.”

Cardon, who lives in Tuscaloosa with her husband and daughter, is working on a new book about environmentalism and race, gender, and able-bodiedness in American literature, inspired by the research she did for Fashioning Character.

“I was really struck by the positives and negatives of the fashion industry,” explains Cardon. “On the one hand fashion can give people the chance to reinvent and express themselves, but there’s another side to its history.”