He came from the old country, a term we are all familiar with. Wilno, Poland, on the Russian boarder. When he was 16 years old, two soldiers from the Russian army entered his family farmhouse to force enlistment of young boys into their army. His father prepared him well for this day by jabbing a pin in his forearm. When the Communists came his father said, “he has no feeling in his arm and needs to be home to work the farm harvest, most of which you take to feed your army, anyway.” The soldiers gave him a long steely stare and left. It was only a matter of time that his father sent him away to escape this poverty and oppression.

On a narrow, winding dirt road there stood a forlorn young man holding two bags of all he owned. He could no longer bear to look at his brothers and sisters, or into his mothers and fathers eyes, solemn sternness, a show of strength, eyes that began to well up greatly. They could no longer speak. Behind him was one room a little more empty, a bed neatly made. The road bent up over fertile rolling hills where he walked to the first great rise. He stopped to look back and found them all still standing there. The road to America was longer and tougher than he dreamed. He would never see them again.

When he was 19 his ship passed the Statue of Liberty, then in long lines of immigration on Ellis Island, he stood with hundreds more in a cloud of uncertainty, and faces of anticipation. America, America the beautiful. He worked as a stevedore on New York’s tough docks, his cap cocked right, and tools of the trade, hook over the shoulder. He soon learned that though you had a job it didn’t mean you could keep it. Ford cars then were sent in wooden crates ready to be shipped. 12 men hooked the crates, lifted and moved them to the line for shipping. If you could not the company always had someone who would.

He married a beautiful girl, Katherine, from his hometown. They had two children, Tony and Lillian, born in Brooklyn. How he loved his wife and his children, exploring all of New York, live theater, Central Park, open markets, movie houses, swimming, the smell of salt water ocean, picnics, Coney Island – the entire city a paradise. “How is this possible?” Especially, the fireworks on the 4th of July, where he taught his children that a free country is an extraordinary gift, a reverent gift never to be treated lightly.

All of them there, New York City in the 20’s, the rich glamour and history of the Roaring 1920’s, never fully realizing it when one is in it. The Great Gatsby, prohibition, speakeasies, Flappers, Italian mafias, Irish mobs, all of them finding a new and lucrative way to make a living, and more than colorful history.

He worked long hours to earn more money for his new family. Katherine, however, began to drink, so much so that when he returned from the docks he would find his children not fed or cleaned. This led to arguing, and more arguing for the first time. Months went by until he came home to find his wife and children gone. Heartbroken, searching places familiar one week and then another. Then followed leads out of state. Nothing. He was lonely and missed his family. Another lead from a lady who said she saw a woman with two kids in a bar in a town south of Toledo just a few days ago. He went there, after three months of searching, someone knew where she lived. The home he found looked empty and abandoned, the front door locked and no curtains. Ready to leave, then thought to look in back where he stood on a crate to look in the window. Both his children were on a hardwood floor in a bare room, alone. The boy without a shirt, and sister crying. He kicked the door in, picked up both his children, who cried and hugged him. Back in New York he won custody, raised them on his own the best he could and did his best to keep spirits high.

The great depression brought severe hardship everywhere. His son Tony had a gang, and began stealing food from supply trucks to feed his and the gang’s families. They were in a warehouse one night doing the same when a guard yelled, “Stop or I’ll shoot!” They ran. Tony was shot through the back and ran a mile before he fell. He was sentenced 5 years in Sing Sing Prison. He was 18. On his first day he was made to kneel in rock salt an hour to let him know how things would be.

Saddened by his son’s imprisonment, Tony’s father left the docks to work as a coal miner in West Virginia. Two years in that job a mule team hauling out coal cars faltered when a harness broke sending the cars back down the grade running, and over his boot. He pulled off the boot to find two toes severed.

The local paper ran a story about Ford Motor Car Co. paying $5.00 a day in Detroit. After moving his family to Detroit’s east side he was employed on Ford’s assembly line, of that he spoke so highly. $5.00 a day. Henry Ford, what a great country.

His son Tony had been released after 5 painful years, Lillian and Tony, a family together again in their new home and a new start. He was a happy man; their home was filled with joy and laughter. Now, the new city of Detroit to explore, Belle Isle picnics, Michigan and Fox movie houses. J.L. Hudsons, western and eastern markets, reminding them all of New York, and fireworks on the 4th of July, giving them time to stop and remember to never take this time for granted.

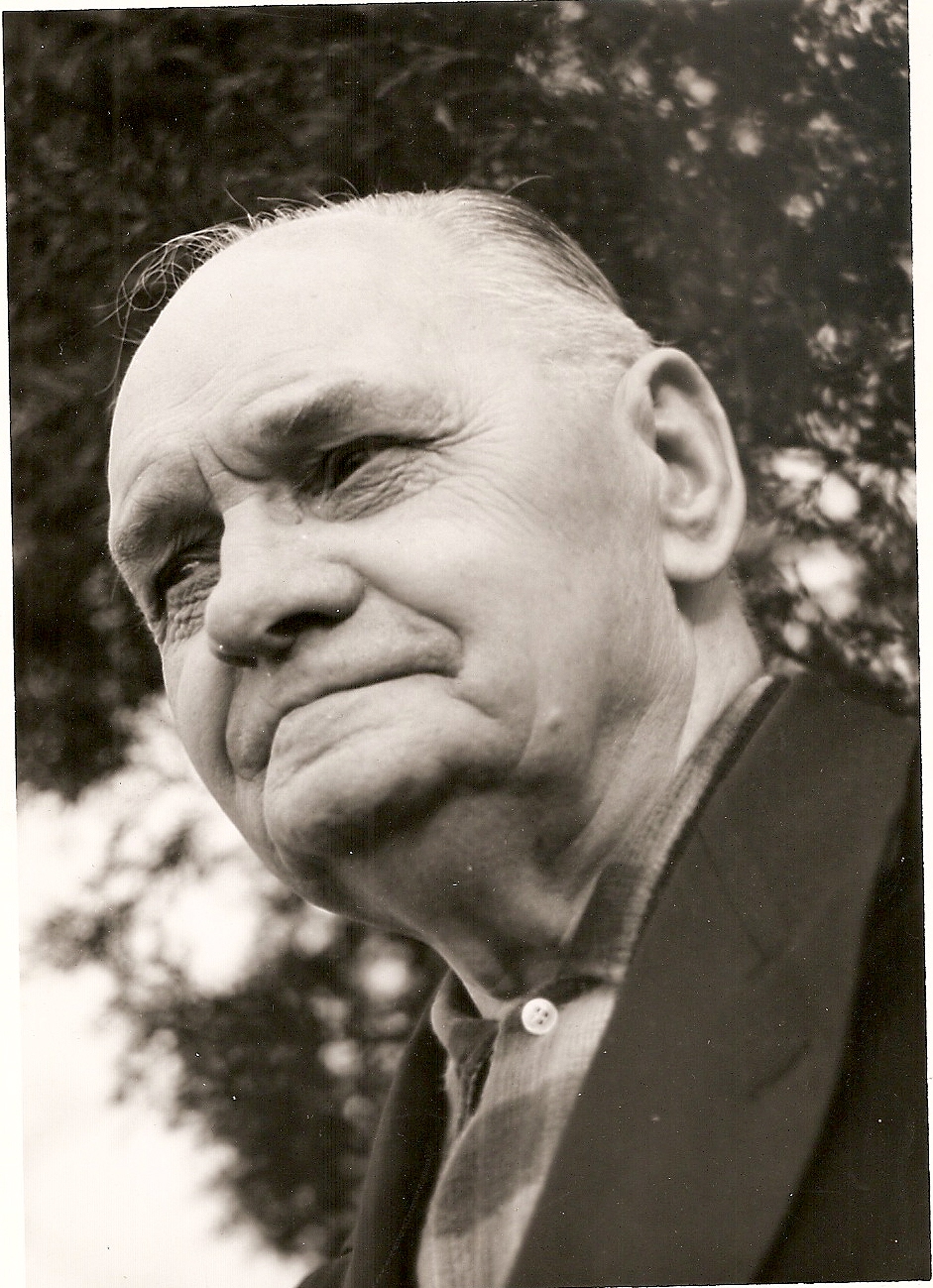

Some years later he was taking a streetcar on Woodward to go to work when his overcoat blew open and a passing car caught it dragging him two blocks mangling his right leg. From that point on he had his cane, a severe limp, a stevedore cap cocked to the side. This is how I remember him, as he walked slowly through the crowd at Eastern Market to find me waiting for him to take him safely home.

In our east side home we had a family dog, a mongrel with a scar over his nose who was the protector of my sister and me. His name was Boy. From our upstairs window I saw Boy netted by the dogcatcher and told him, my Grandfather, who grabbed his cane and a broom. He limped his way down, confronted the dogcatcher and said, “that is our dog!” The dogcatcher said, “he doesn’t have a license and I am taking him.” My Grandfather said, “Do you have a license to take him?” He replied, “I don’t need one, I work for the city”. My grandfather politely smacked him over the head with the broom, then let the other captured dogs in the truck free. The dogs, Boy and my grandfather were happy.

Years later we all moved to Ferndale, a corner home off 9 Mile and Republic. My Grandfather was called the “old man” by all of our family, out of respect. He was showing me pictures of his family back home. Brother, sisters and their children. Lean, hard, wearing hand me downs on the young children, all with gaunt looks of hopelessness. He lived, leaving behind communism and its oppression. His eyes stared at the images, unable to contain their sadness and despair.

When he was in his 60’s his mangled leg lost circulation and he finally had to have an amputation, just below the knee. Months later it became infected. It was done a second time above the knee. The family asked if he would consider suing the hospital, Beaumont, in fact. He said no, “I don’t think the good doctor would do this intentionally”.

During that time he had been going to Detroit to study for many months. At the end of one day, he called me upstairs to sit by his little table at the window, where I sat many years learning how to listen and how to ask. He pulled out a paper and, carefully, unfolded it. He said, “I am now a citizen of this great country”. I watched him slowly, as his eyes began to well up. The old man, my Grandfather, who raised me hard but well, his own generous nature giving me the street sense and all the tools I would ever need. He left this, his earthly place, on July the 4th (1965).

Tom Brank is a film producer and writer living and hiking in the Leelanau Peninsula, Mi.