Writer Anthony Brancaleone Celebrates Detroit’s 313 With Homeboy Raconteur

__________

You looking for me?

After a couple weeks of tracking him down I was sitting at my desk, early morning, sipping coffee and pushing through a long list of emails. Paper notes, Moleskins, pens, business cards, cell phone and a key to a long forgotten lock awaited direction, but I remained focused on the subject bar.

You looking for me?

Opening the email I discovered a single word.

Charlie

Clean, concise, no punctuation.

Yeah, I’m looking for you Charlie. Thanks for the reply. Would you like our first meeting to be over breakfast, lunch or drinks? On me, of course.

Two days later came his reply.

What do you need?

I need your counsel and a little bit of your time. Then, I detailed the subjects I wished to discuss. There were several.

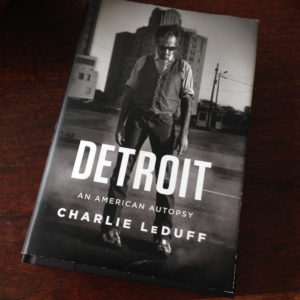

At the top of the list was Charlie LeDuff’s Detroit: An American Autopsy, a book that was published in February 2013 but that I had not read until one year later. In fact, I am pretty sure I was trying to avoid the work, convinced it would be more of the same in a line of opportunistic trite that had been filling Detroit’s deepest recession. It wasn’t until an acquaintance of mine, a well bred transplant from the east coast, Mr. Tick had allowed me to borrow his copy that I finally gave this Pulitzer Prize winning reporter from the New York Times a chance.

LeDuff’s book hit me immediately. Though his Detroit story was different from mine the parallels affected me deeply. I was sure his words touched others as well. LeDuff spoke in first person sharing difficult moments in his life from the tragic loss of his sister to the financial struggles of family and friends as they survived a city strewn with corruption.

An American Autopsy is filled with burning houses, underfunded fire and police departments, vice, greed, and frozen death. Yet, there remains a glimmer of hope, one usually reserved for those who sing the deepest blues, that says everything is going to be alright, Detroit is going to survive.

LeDuff handles the city the way Steinbeck handled his “Okies” in Grapes of Wrath. And, like good Pulp, Charlie entertains with a combination of grit, grace and humor. An American Autopsy, while flawed, is a classic American tale.

A few days passed and Charlie emailed his phone number. We exchanged voice mails and then I caught his series The Americans online; the episode where LeDuff drinks beer with Kid Rock on the Detroit River over the 4th of July. While there was not much going on in the piece it did seem like a nice way to pass the holiday. So, I called Charlie again and invited him out for a drink at his earliest convenience.

July 24th is Detroit’s birthday. This year, however, was particularly special. Founded in 1701 by Antoine Laumet de Lamothe Cadillac meant that Detroit was turning 313, a number that coincides with the city’s iconic area code. For those into numerology or other alignments it was something else to grab onto in order to pull a community up by its bootstraps.

On this afternoon I was in black suit and tie en route to meet Mr. Tick at The Whitney for cocktails and a little conversation when the phone chimed inside of my breast pocket. I answered without looking to see who it was.

“Hey, this is Charlie.”

His voice was raspy and sounded very relaxed.

“Sorry I couldn’t get with you earlier but . . .” He continued to outline his last few days. “I wanted to let you know that I liked the way you came at me and how you described your work as DIY. I’d be happy to get a drink.”

“We were two Martinis in when Charlie arrived wearing Jeans, white button down, and signature American flag cowboy boots. “

“That’s cool,” I said.

And, then I rambled off my admiration for his book, and how it was an important document, and that I really was moved by his storytelling, and all of those things a fanboy rather than a reporter would say. I couldn’t help it. I meant it. And, too often the good work of artists in this town gets shunned.

“What are you doing right now?” Charlie asked.

“I’m on my way to a meeting at The Whitney in a suit and tie,” I said. “I’d like to meet you later in a real bar to discuss your book.”

“I’ve got some time today, and The Whitney is a ‘real’ bar, and its Detroit’s birthday, so why don’t I come down and we’ll celebrate.”

“Alright, Charlie,” I said. ” But, I have to tell you I’m not really prepared, and I’m in a suit, and . . .”

“Don’t worry about it,” Charlie said. “I’ve got some things to wrap up here at the station, then I’ll be right down.”

My associate, Mr. Tick and I had a small room off to the side of the bar on the third floor. We were two Martinis in when Charlie arrived wearing jeans, white button down, and signature American flag cowboy boots. He sat placing his cigarettes and phone on the table, and ordered a tall beer. My meeting with Mr. Tick came to an end and we entered into the usual pleasantries with Charlie.

Our bartender arrived at table with two Martinis and Charlie’s beer. We gave a toast to Detroit, wishing it a happy 313, then moved into conversation about hipsters, the late Detroit artist Michael Kelly, and the two million dollar MOCAD installation that sits in his name directly across the street from The Whitney (one that fails to impress Charlie), and Detroit artist Tyree Guyton.

LeDuff champions Guyton as “one who at least did something interesting in a neighborhood that was otherwise dying; the ‘mass hypnotism’ of Detroit’s rebirth versus the reality of life on the streets,” and so on.

Talk moved to American Autopsy and how LeDuff’s first publisher didn’t like it: “Well, we’re at loggerheads then because that’s all I’ve got,” Charlie told the publishing house. Then he gave them back their money.

The band at The Whitney Garden Party plugged in and Detroit post alt rock flooded the room where we were seated. Summer in Detroit. I suggested that we move to another room, because I wasn’t sure I was going to be able to record from the sound.

“You’re recording this?” Charlie said.

“I need it for reference,” I replied.

Charlie seemed put off.

“I don’t want to tell you your business, but there are ways you do things,” he said.

“I understand,” I replied. “But, I thought we cleared this on the phone when I was in the car? I said I wasn’t prepared for an interview and that I will have to use my phone to capture our discussion.”

Charlie was cool, took it in stride, but continued to bust my professional balls for a while. I felt genuinely bad about the misunderstanding but couldn’t escape the irony of LeDuff, a reporter who made his bones, in part, by breaking the accepted rules of contemporary journalism, schooling me on the process. Still, if it wasn’t made perfectly clear that he was being recorded then I stood in the wrong.

“You know what’s funny?” Charlie continued. “If I had not gone out of here (Detroit), intellectually that book couldn’t have been written; spiritually that book couldn’t have been written; everybody needs to go out and find the bigger world; find out where your place is; the things you harbor, the bullshit you’ve been taught. And, you need to compete. Professionally, that book is not getting published. ‘You need an agent’. You have to go out there in order to make it. What’s nice about it is that the place called ‘Detroit’ vouches for it.”

He picked up his cigarettes and moved toward a closed window.

“Smoke?” he asked.

With the casualness he might display at home Charlie opened the window and pulled out the screen.

“Sure,” I said.

We continued talking and blew out into the open air.

“Isn’t this illegal?” inquired Mr. Tick. He was still seated, wearing his pop up collar and smiling into his Martini.

From The Whitney we moved to the rooftop terrace that Mr. Tick shares with the tenants of a Midtown building. We opened a bottle of wine and a pint of whiskey. Glasses filled, Charlie lit another cigarette.

LeDuff described his book as a “roadmap of journalism and articles” that he pulled together from his past. He took “family stuff” and other stories that were good, and then asked, “Where’s the hump?” He realized the hump was the “frozen guy” who was found several floors underground in the depths of an abandoned building. That’s where he began his tale.

“It’s better to be forward and plain spoken,” Charlie said. “If you have a book with Detroit on the cover the book better have balls. Keep it spare, clean, with space between the sentences so you can place your own in. A reader can think about his own life.”

“If you have a book with Detroit on the cover the book better have balls.

Damn, if the city isn’t beautiful when the sun is setting just so. Amber hues were playing off Detroit’s storied past, illuminating the skyline behind LeDuff while he dropped pearls about his process of storytelling.

“Do you have a brother, an uncle?” LeDuff said, rhetorically. “A blue collar guy is not a dope, he’s a worker. It’s ok to talk about it – the Detroit Recession – it’s not dirty laundry, man. We’re more alike then we know.”

A couple hours later, Charlie invites me over to his house. Mr. Tick had to call it a night. I was feeling a bit spent from a full afternoon of drinking, and my recent development of allergies had begun to kick in; watery eyes, sinuses, migraines, and other shit brought on from God knows what. But, I agreed and followed Charlie in his vintage black Cadillac along the freeways to Pleasant Ridge, stopping first for a bottle of Jamesons and a six pack of Carlsberg, before making it to his home.

We entered Charlie’s house through a side door near the driveway that led into the kitchen. He opened the whiskey, cracked a couple of beers, and moved us to a deck in his back yard. We spoke more about his book and the fine photographs in the back by Danny Frazier.

“I wanted Danny’s photos to be their own story, a supplement to the book,” LeDuff explained. “I hate it when there are pictures in the center. It ruins the flow.”

My head was spinning from drinks and pollens.

In his book, LeDuff spoke both of the sounds of factories and of the calming affect of the sea. I wondered if Charlie chose this location to live because it bordered 696, which in the after midnight quiet emitted a tide of mechanical waves produced by the steady flow of traffic; a calming sound not unlike the sea, a subconscious tie to his past.

In the post industrial wasteland of the Detroit Recession there were still parallels to be drawn between natural and manmade tides. And, nowhere in America was the struggle between Man and Nature more acute than the Motor City – a struggle that eventually became Man verses Self for anyone who was trying to survive.

We drank from the bottle of Irish whiskey and finished a few Danish beers.

My head hung low, eyes closed, as I listened to the tide. In my mind, I flipped through passages of American Autopsy, then rummaged through some of the junk drawers of my past before allergies began to plague me, producing dizzying pressure behind my eyes and a stream of water that ran intermittently down my cheeks. For Charlie, I must have looked like an addict or an emotional wreck.

“There are ways you do things,” Charlie said.

He sipped from a bottle held loosely in his hand.

“I’m not saying I’m mad,” he continued. “But, there are just ways you do things, man.”

Detroit: An American Autopsy (Amazon)