by Harry Onickel

Yes, I did. I read A Little Princess by Frances Hodgson Burnett. No, it’s not a book that I would have thought to read on my own. But I read it. I blame television. And Scholastic Books. And The Secret Garden, also by Frances Hodgson Burnett. I wasn’t planning on reading The Secret Garden either. I’d heard of it. I knew it was a children’s classic. So I ordered it from Scholastic. Then I read the opening line: “When Mary Lennox was sent to Misselthwaite Manor to live with her uncle, everybody said she was the most disagreeable-looking child ever seen.”

How do you not continue reading after that opening?

“Call me Ishmael.” Yeah right. Not even close.

In the interest of efficiency, I read the book to my fourth graders. When I began, I figured I would read to them until they lost interest, then I would finish on my own. There was no way they would last for over 300 pages of not-written-down-to-children prose in addition to my insistence that we talk about the book now and then.

But they did. They listened. They were able to discuss the book intelligently. We may have even done some writing about the book, I don’t remember. It went so well that I read it again over the next few years. And for the most part, students enjoyed it.

But, back to A Little Princess. In the Scholastic catalogue, I noticed it too, was written by Frances Hodgson Burnett. This was not the only enticement. Shirley Temple starred in a movie version in 1939, her first movie to be filmed in Technicolor, something I was unaware of, as I watched it in pieces over many showings back in a bygone era. These were the days when my family had one black and white TV set. Until Dad sprung for a second set, we only had four channels. The new set, with the latest in television technology – UHF – had eight – kind of. Channel 20 (or was it 62?) never came in very well. To change the channel we turned a dial on the TV, which meant we had to get up and walk all the way across the room to do it. And then go all the way back to the couch, having had to walk uphill both ways through three feet of snow. Actually the snow was mostly on channel 20 (62?).

In those early TV days, there were movie themed shows. In Detroit, we had local movie hosts who helped shorten our attentions spans by constantly interrupting the old movies they showed with commercials and their own blather. There was Rita Bell’s Prize movie on weekday mornings. Weekend afternoons featured Bill Kennedy. After school we came home to cheesy monster movies. And at some other time in the day, we watched Three Stooges shorts. Late at night (too late for me but I heard from friends) there was Morgus Presents. Saturday (or was it Sunday?) mornings there always seemed to be a Shirley Temple movie on. As a child, Shirley Temple was one of the most popular stars of the 1930s. In movie after movie, in-between singing and dancing, she faced and soundly defeated adversity with a combination of innocence, charm, and spunk. Everybody loves spunk, right?

Ram Dass and Sara Crewe

Why do I remember A Little Princess over all of the other forgettable movies? I don’t know. Maybe it was the exotic location – London England at the turn of the 20th century. Maybe it was the drama and intrigue of Shirley Temple rising above her tormentors. Or was it the absurdity of her secret, turban-clad helper from across the way, filling her unheated garret with luxurious furniture and linens and her bare larder with wonderful delicacies? Possibly it was the incongruence of Temple’s American accent and Becky’s bizarre Cockney (?) accent as they struggled through the abuse heaped on them by Miss Minchin and the wealthy, spoiled schoolgirls. It could have been the impossible heart-wrenching ending where Temple, as Sara, discovers her father, whom everyone thought was killed in the Boer War. He’s in a daze, calling softly for Sara. At first he doesn’t recognize her, which leads to more heart-wrenching tears and Dad finally coming out of his war-induced trauma to reunite with his “little soldier” and rising out of his wheelchair to salute Queen Victoria. Or have I silently been raging for all these years, that Becky, who helped little Sara when she was cast into her servant’s role after her father’s supposed death, and who went to the hospital with Sara to help her find her father, was left behind and ignored by Sara, Dad, and Queen Victoria? Our last view (as I imperfectly recall) of poor Becky is in the clutches of the evil Miss Minchin, whom we know is going to force her back to being a lowly scullery maid and will probably abuse her even more for helping Sara to escape.

The ending of the book is much more satisfying, but as syrupy. Becky is adopted along with Sara by the Carrisfords (who don’t appear in the movie). Mr. Carrisford is Captain Crewe’s friend and investment partner, who just happens to move into a home directly across the street from the school and whose children, Sara, by coincidence, meets earlier in the book. And in the book, the fellow in the turban is the Carisford’s Indian servant, Ram Dass, who takes pity on Sara and Becky and acts as their secret Santa.

Oh yeah, Dad is really dead in the book. And it wasn’t because he went off to bravely fight for queen and country. See, there were these diamond mines that Carrisford convinced him to invest in, which turned out to be fraudulent. After being left penniless, both men come down with “jungle fever.” Dad dies, Carrisford survives.

Sara is now also left penniless. Not able to pay her school bills, Sara is forced to join Becky in her unheated attic and earn her keep as an errand girl. Sara suffers much abuse from Miss Minchin but demonstrates her virtue by refusing to be humiliated. But then! Unbeknownst to Sara or Miss Minchen! The diamond mines are real! Carrisford, feeling tremendously guilty over all of this, leaves his family to travel the world in a vain search for Sara in order to give her the diamond wealth she has inherited.

After more ridiculous plot twists, everything is figured out, loose end are tied up, and happy endings abound. Unlike the movie ending, Becky is not left hanging. She gets to be Sara’s maid. So maybe Becky isn’t exactly “adopted,” but Sara, being so gracious and kindly, we know that Becky will be well taken care of.

The end.

I don’t know if Frances Hodgson Burnett had children of her own, but she certainly went to extremes when it came to fictional parents. Mary Lennox suffered with two completely neglectful parents who left her in the care of servants while they made the rounds of various parties. Then they died. Burnett makes it clear that it is this neglect that turns Mary into the cruel, spoiled brat who is forced to find her inner strength and empathy when she meets her cousin, who is even more wretched.

Sara Crewe’s father doted on her to the point where one wonders how she wasn’t smothered by his love. Then he died. When her comfortable world is upended, she shows an inner vigor beyond most of the adults in the book. She demonstrates decency and compassion to those who are in even worse shape than she is in.

Being a dad myself, I like to think that a secondary theme of both books is the importance of parents in their children’s lives. One never knows when that bell is going to toll for thee, so thou hast better prepare thy children well. Are either of these books real or believable? Who cares? As Zippy the Pinhead once said, “Reality is a sandwich I didn’t order.” Neither did Burnett, and I only occasionally nibble at mine. With so many fathers today taking the Lennox route and abandoning their children, I have to accept that it was her father who gave Sara Crewe the strength she needed to overcome her fall from luxury. Maybe I’m reading too much into these stories, but fathers still need to stick around and raise their children.

Non sequitur: Ram Dass, is Sara Crewe’s mysterious turbaned benefactor and Carrisford’s Indian servant. In real life, Ram Dass used to be known as Richard Alpert. Alpert, former Harvard professor, friend and LSD experiment partner of Timothy Leary, was given the name by his guru, Neem Karoli Baba, whom he met in India. Ram Dass means “servant of God.” Synchronicity?

Maybe.

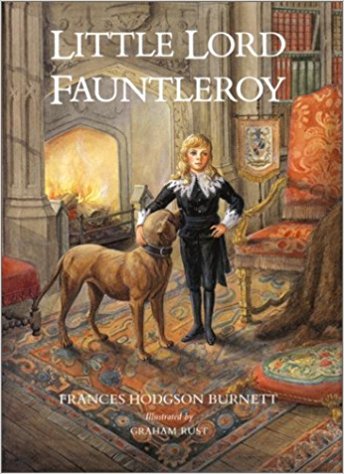

Frances Hodgson Burnett’s other famous children’s book was Little Lord Fauntleroy. It doesn’t have a great opening line like The Secret Garden. It does however create another avenue for a young Burnett hero facing a parent’s death to meet the challenge of hard times. Am I going to read it? Probably not. Had Shirley Temple starred in the movie version, I might, but I don’t think Depression-era America was ready for cross-dressing children.

I’m Harry Onickel. I am a reader. I always have been. I like to think that between reading for all these years, fiction and nonfiction, high and low culture, classics and trash, the acceptable and the dangerous, and just being around for a bit, I’ve learned one or two things and perhaps gained a bit of perspective. In addition to learning, reading makes me wonder. Lately, I’ve been wondering – what lies behind the mask? My blog, occasionally updated, is The Teacher That Exploded.