By Joe Neussendorfer, Aff.M.ASCE, ESD

The Midfield Terminal at Detroit Metropolitan Wayne County Airport (DTW) opened to the public in February 2002. It was named after Edward H. McNamara, former mayor of Livonia, Michigan who went on to be elected Wayne County Executive. Mr. McNamara was a consummate economic developer. As the mayor of Livonia, he aggressively sought new industrial and manufacturing facilities for the city. He continued this mission as Wayne County Executive. He fought hard and long to secure the required federal funding for the new $1.2 billion terminal.

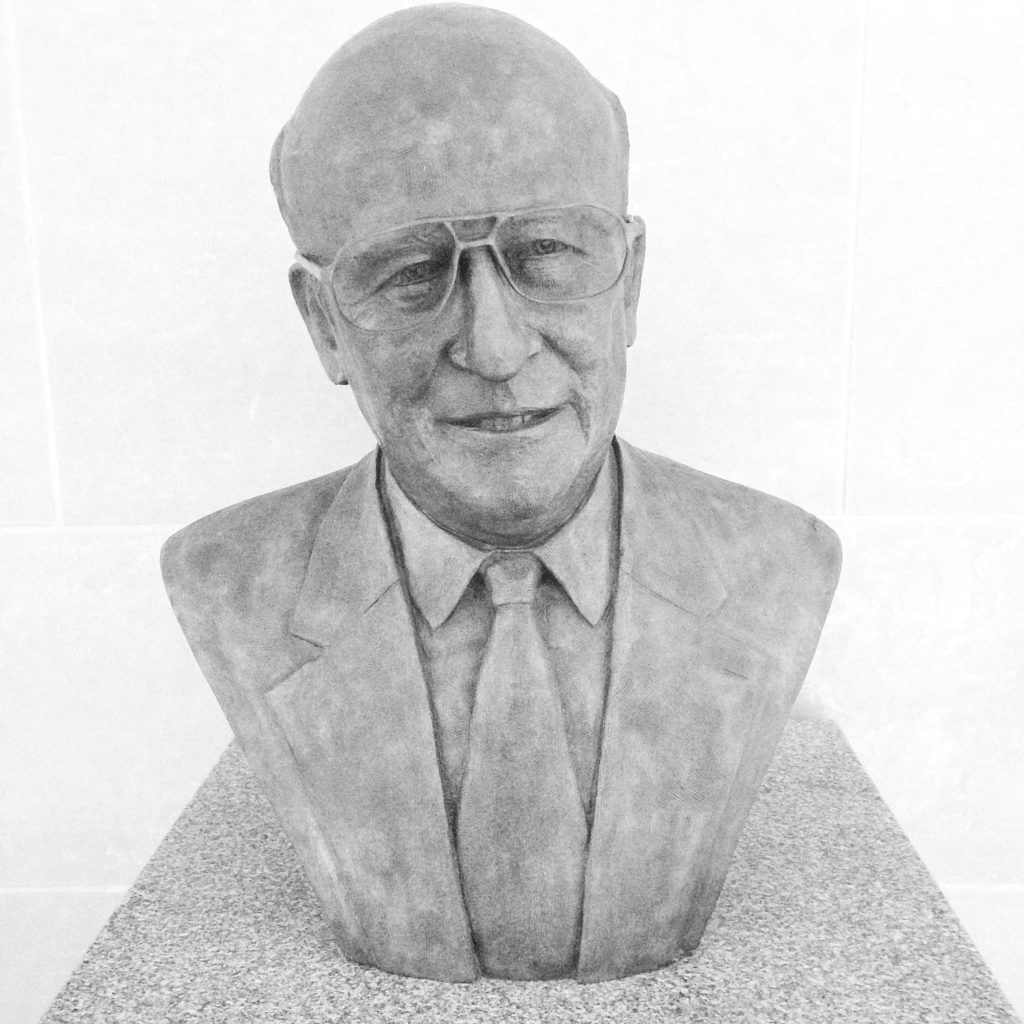

Legend says that air travelers who rub the head of Edward H. McNamara’s bust located inside DTW McNamara terminal will have a safe flight (image: AB)

The new Midfield Terminal was designed by Architect David King, chairman of the Detroit-based architect/engineer SmithGroup (now SmithGroupJJR). King received his bachelor’s degree in architecture from the University of Texas at Austin, and master’s degree in architecture from Harvard University Graduate School of Design. He also designed the MCI Center Sports Arena, Washington, D.C. and the Time Life Headquarters in Alexandria, Virginia.

Architect King, at the time, said “From its small thoughtful conveniences to its first-of-a-kind Express Tram, we feel the terminal is going to quickly catapult Detroit Metro Airport to world leader status.” His words rang true. The McNamara Terminal has far exceeded expectations and travelers from around the world still marvel at its amenities.

The design of the terminal started with a comprehensive review of dozens of major airports both in and outside the U.S. The SmithGroup design team visited airports in Munich, Prague, and Amsterdam, among others, but knew Detroit needed its own unique solution.

According to SmithGroup, “the site of the new terminal, located between four existing runways and almost cigar shaped, posed a challenge for designers. With such a tight, constrained site, it was clear that the new terminal would need to be a highly linear building, and of exceptional length to accommodate its ambitious program.” The resulting building form is a main concourse that is a single pier, nearly one mile long—a contrast to the more parallel concourse used at major U.S. airports such as Atlanta’s Hartsfield Airport and Denver International Airport.

The construction on McNamara Terminal

Inside, the architectural features that reflect “world class” status are immediately apparent. As passengers step in to the ticketing area, the ceiling soars to a height of 36 feet, giving visitors a sense of spaciousness. Above, the exposed king-post truss and framing system defines the soaring arc-like roof system that provides for column-free spans up to 87 feet. According to the SmithGroup’s designer, passenger circulation was a top priority when designing the new terminal. “ It is simple and straightforward, void of the confusing turns common in other airports.” The terminal’s design gets people where they want to go, fast, an important attribute when one considers its expansive size, King said.

Because of the elongated shape of Concourse A, designers knew an innovative mechanism would be needed to move passengers through the 4,900-foot length. SmithGroup’s solution was to bring a fully enclosed automated people mover into the concourse, which hadn’t been done in any other airport in the world. Rather than moving passengers underground or outside, the Express Tram quietly moves on a cushion of air on the mezzanine level of Concourse A, 21 feet above travelers. An open, tube-shaped structure that surrounds the track was designed to help further minimize the tram’s sound.

The McNamara Terminal also features two architectural highlights. One is the water feature, which serves as a “center stage” focal point at the midpoint of Concourse A where it meets the central link. It features the use of choreographed laminar steams to create a kinetic display that can vary from tranquil and contemplative to playful and energetic. The other architectural highlight of the terminal is the passenger tunnel that connects Concourse A to Concourses B and C. The one-of-a-kind, 800-foot passenger tunnel creates an ever-changing, mood enhancing sound and light environment. Comprised of sculpted art glass panels, advanced lighting technology and computer-programmed synchronization of custom music and light, the tunnel gives passengers who pass through it the impression that they are not underground but “in another world.”

One significant aspect of the midfield terminal construction that most Detroiters do not remember is the massive, recordsetting achievement performed by Detroit General Contractor Walbridge Aldinger and its team consisting of Posen Construction, Utica, Michigan Foundation Company, Trenton, Cross Enterprises, Inc., Melvindale, Quality Resteel, Brighton, Ric Mann LEDDs Development, Sterling Heights, Blue Circle Cement, Marietta, Ga.,and Euclid Chemical Company, Cleveland, Ohio.

All of these firms participated in a record-breaking and largest “continuous concrete pour” work to support the new midfield terminal. 20,917 yd3 (16,000 m3) of concrete was placed in a time span of 22 hours and 57 minutes on May 15-16, 1999 for the mat foundation of the North Tunnel project at the airport. A 4 ft. (1.2 m) thick foundation, 950 ft. (290 m) long and 150 ft. (46 m) wide, was needed for a 30 ft. (9 m) deep tunnel completely below grade. The finished tunnel supports the load and provides resistance from impact for a jet runway and permits through access for three roadways into the midfield terminal.

To deliver that much concrete quickly to the job site, 150 concrete mixer trucks completed 4600 round trips from six different batch plants, three on site, and three off site, which combined to supply concrete at an average rate of 1160 yd 3 (890 m3) per hour; 300 drivers were used in two shifts.

The McNamara Midfield terminal is truly an architectural and engineering marvel that all Detroiters should be extremely proud of!

(Writer Joe Neussendorfer has written about Detroit’s construction heritage for 35 years, and is an Affiliate Member of the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) nationally and its Southeastern Michigan Branch.)