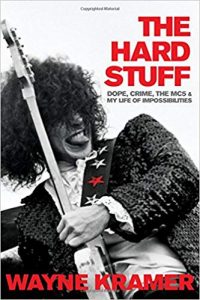

Published by Faber Social

According to Eric Hoffer in his book, THE TRUE BELIEVER, when discussing society’s undesirables and their role in forcing change, “The superior individual . . . plays a large role in shaping a nation, but so do individuals at the other extreme – the failures, misfits, outcasts, criminals, and all those who have lost their footing, or never had one, in the ranks of respectable humanity. . . They see their lives and the present as spoiled beyond remedy and they are ready to waste and wreck both: hence their recklessness and their will to chaos and anarchy.” This brings us to Wayne Kramer, who gives us a tour of his life in his memoir, THE HARD STUFF, Dope, Crime, the MC5 & My Life of Impossibilities.

Not to insult Kramer, but he embodies Hoffer’s definition of “undesirable.” He grew up in and around Detroit, one of the United States’ “least desirable cities”. He engaged in petty crimes in his youth and in bigger crimes as an adult. He founded and played guitar for the MC5, a band whose battle cry of “Kick out the jams, motherfuckers!” while energizing their teenage audience, left older generations warily scratching their heads. His band mates were other working class kids who, like him, were influenced by undesirable music; free jazz, R & B, blues, and early rock and roll, mostly created by black, therefore undesirable musicians.

The band’s mentor/manager was John Sinclair, Detroit area poet, self-styled revolutionary, and general thorn in polite society’s side. Under Sinclair’s guidance, Kramer and the MC5 saw themselves as revolutionaries. In support of the Black Panthers, they formed the White Panther Party, with part of their 10-point program calling for a “total assault on the culture by any means necessary, including rock and roll, dope, and fucking in the streets.”

In the late 1960s, Sinclair, the White Panthers, and the MC5 did scare their elders. This young generation was rebelling in ways their parents had never seen, even though for most teens it was all a pose. The rebellious nonconformity was simply a way to conform. The music though, coming from the MC5, and other Detroit area bands was frighteningly honest.

While they were too revolutionary for parents, police, politicians, and record companies, the MC5 weren’t nearly revolutionary enough for some of the more extreme, and possibly insane revolutionaries. They were physically attacked during a New York show by a group calling themselves, ironically, the East Village Motherfuckers, who accused them of being sell-outs for not acquiescing to all of the Motherfuckers’ demands. Kramer was verbally attacked during a radio interview by a member of Students for a Democratic Society as being a faux revolutionary only in it for “fame and profit.” Then, as now, and as always, true believers turn on each other for not being true enough. There was also a falling out with Sinclair after his infamous drug bust and imprisonment. They tried to recruit other managers, but the band was, as Kramer admits, unmanageable.

While the MC5 was doomed to a short but intense life, they, and Kramer, had a tremendous effect on what would become 1970s punk rock, originally a small movement, but one that opened the door to metal and new wave, which led to alternative, grunge, hardcore, indie, regional punk movements, and other mini and micro musical genres. Their reckless stage and record energy helped create both the punk and metal templates. They were heralded by later bands like The Clash and the Damned. Nick Lowe told Kramer, “I stole everything from you, Wayne.”

As Kramer writes about the MC5’s second album, “Back in the USA”, which was released in 1970, “This record was exactly what the punks were looking for; it was sharp and to the point, with short songs and a sarcastic perspective. The record was a rejection of the grandiose, overindulgent, superstar rock culture of the sixties.” Why didn’t the punks pick up on their first record? According to Kramer, it came out too early (in 1969), and the record company never promoted it. Of course, use of the word, “motherfucker” on that first record did not endear them to the record company, department store executives, or parents.

The MC5 went the way of many other high energy, high debauchery bands. They were only able to put out three records before self-destructing. Some bands that embraced the same ethos were able to rise out of the ashes. There is a learning curve that they were able to intuit and follow in order to survive. Not so, the MC5.

On a personal level, Kramer also worked for a long time on self-destruction. He spent a lot of time and money on alcohol and various drugs. Beginning with marijuana as a teen, he writes as if he tried them all, sometimes all at once. One night, in addition to heavy drinking, “. . . I took some acid and then a lude, then snorted some coke . . .”

When writing about his childhood, Kramer talks about enjoying feelings of safety and security at certain times and with certain relatives. As an adult, he eschewed both safety and security. Substance abuse, crime, and rock & roll have never been the tickets to a secure existence.

Admittedly it takes a certain amount of intestinal fortitude, or “balls” to live that rock & roll rebel life. Most are too timid for that kind of uncertainty and risk. We make a living, conform to a daily schedule, collect a dependable paycheck so that we have a decent place to come home to and store the stuff we accumulate; no sleeping on the floor of a rock & roll crash pad for us. We might play at rebellion by driving over the posted speed limit or by calling in sick to our job when we’re (shhh) actually feeling fine. To demonstrate an imagined bravery, some Suburbanites will, loudly and boastfully, but carefully, head down to a bar or club in a seedy part of town.

Deep down, there is a certain amount of jealousy the establishment has toward the type of person who is free enough to not be dependent on that security and societal approval and is willing to master an instrument, form a band, teach band members to play, stay up all night rehearsing, or discussing politics, or getting loaded or laid, or all of the above, while living on peanut butter sandwiches because that’s their only affordable food. That establishment admires their skills and tenacity, envies their life style, but condemns their evil ways because it isn’t brave enough to face the discomfort that comes with that freedom.

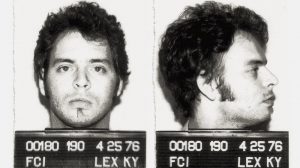

Kramer had a second career as a criminal. After getting caught in a heroin bust, he spent time in prison. Even after prison, he engaged in criminal activities and continued to abuse drugs and alcohol. He had a third and intrinsically rewarding career for a time, as a carpenter. Through all of it though, he pursued music. In prison, he played guitar with jazz trumpeter, and musical mentor, Red Rodney, to whom he pays a beautiful tribute when describing their musical and prison relationship.

Kramer is one of Rolling Stone’s top 100 guitarists. That is mentioned on the book’s cover flap, but it is important to note that he is a brilliant guitar player and is extremely talented in many aspects of creating music. In spite of his addictions and set backs he was able, with some lapses, to maintain a career in music.

I hate to mention this because I don’t want to sound cliché, but his is also a story of redemption. Kramer triumphs over his demons and, with help, is able to emerge on the other side of addiction to continue his music career and form a loving family. Not everybody who enters that world emerges victorious. The mortality rate is frighteningly high. Kramer loses a number of friends and associates along the way.

Strength carries him through, but there is also some luck involved, as when he wakes up face down in a pool of his own vomit, rather than dying face up as Jimi Hendrix did. I’ve heard that addicts will seek treatment when they’ve reached bottom, a state I’ve always pictured in a physical form. When Kramer finally reaches that Zen moment, he is just coming off of a successful European tour with one of his post-MC5 bands. He creates an incident on the return flight, and, “By the time I landed at LAX, I was crying my eyes out. Crushed emotionally, physically, and spiritually, I was incomprehensibly demoralized. . . . It wasn’t an economic bottom or a physical bottom, although it could include those conditions. It was a psychic and emotional bottom. It was the realization that everything you tried just kept blowing up in your face.”

Once clean, and after a hugely successful 2004 world tour with surviving MC5 members, Dennis Thompson, Michael Davis, and many guest musicians, Kramer is approached by fellow musician, Billy Bragg, who runs an initiative that supplies musical instruments and lessons to help rehabilitate prison inmates. The charity, Jail Guitar Doors, is named after a Clash song, coincidentally written about Kramer. Kramer signs on, and a few years later, with the help of other American musicians, starts Jail Guitar Doors USA, its mission, “to help rehabilitate prison inmates by teaching them to express themselves positively through music.”

At memoir’s end, Kramer has the family unit he didn’t have growing up with his mother and an abusive stepfather who took over from Kramer’s absent alcoholic father. He’s 70 years old. He’s still writing, playing, and recording music. He’s a dad. When we look back to the days when music changed from drug-addled hippies playing endless, meandering solos, to drug-addled punks slamming through an entire set list in less time than it takes to listen to an endless meandering solo, we usually picture a Johnny (come lately) Rotten.

But, we should picture Wayne Kramer.

Hi, I’m Harry Onickel. I am a reader. I always have been. I like to think that between reading for all these years, fiction and nonfiction, high and low culture, classics and trash, the acceptable and the dangerous, and just being around for a bit, I’ve learned one or two things and perhaps gained a bit of perspective. Lately, I’ve been wondering – what lies behind the mask?