Harry Onickel

Why am I learning algebra? I’m never going to use it. And if my algebra is never going to be used, why would I bother with even higher math?

Many of us asked those questions long ago in high school. Today, as adults, people are asking why they should put their own children through the agony of algebra. And geometry. And trigonometry. And calculus. When are they ever going to use that stuff? I know someone who found his old calculus notebook twenty years after graduating. He couldn’t make heads nor tails out of it. None of it made sense. So why bother?

On the other hand, we’re told that schools must teach the arts. Students need music, painting, drawing, theater, poetry. Well, maybe not poetry. Is poetry even taught any more? How many students are going to use poetry? As an adult, can you tell me the last time you used poetry? Or theater? Or music? I don’t mean listening to music, I mean using it in your everyday life. Just like we have scientists and engineers who use higher math, we have musicians, music producers, songwriters, and others who do use music. But most of us don’t. I have a reasonable-sized record and CD collection. I listen to music, but I don’t use it. When it comes to drawing, are you kidding? Raise your hand if after all of those public school art classes you still “can’t draw a straight line.” The cry goes out though: schools must teach the arts! Students must be able to do more than just pass a test (assuming they can pass the test).

And it’s true. Education has to be more than test preparation. The fact that so many people insist that arts must be in taught in school shows that we want our children to learn more than just what is assumed to be practical. We want their lives to be enriched. We want the world to be open to them. They shouldn’t be circumscribed by mere sensible considerations.

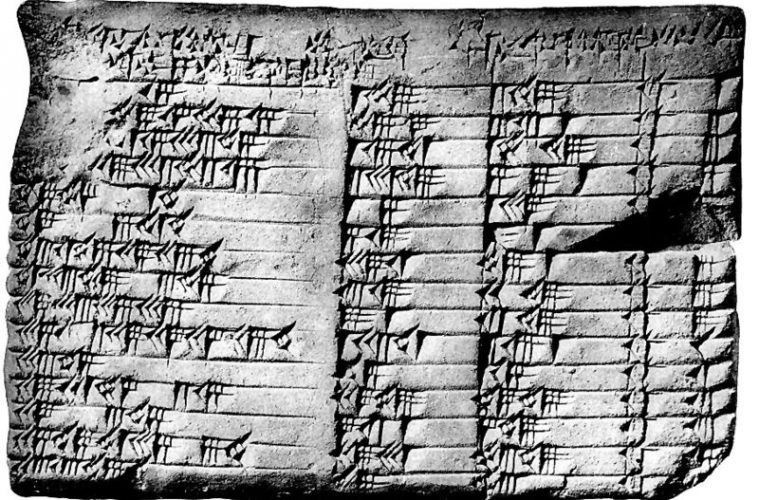

Hellenistic mathematician Euclid details geometrical algebra

But how do you know your kids are never going use algebra? Let’s face it, none of knows what we or our kids are going to need or use in the future. We do know that for many of us, when you get past algebra, math takes a turn for the really difficult. Not everybody has a “math brain,” and for some students it makes sense to stop there, or maybe at geometry. But be careful where you place that stopping point. Be very careful in deciding what children don’t need to learn. A long time ago, the educational experts at our big time teachers’ colleges decided that spelling and the mechanics of writing weren’t really important and shouldn’t be explicitly taught. Students shouldn’t get “bogged down” in spelling and other inconveniences. They should just write. No matter that their writing is incomprehensible, putting something on paper counted more than communicating thoughts. As we’ve seen from the tests everyone loves to hate, and from speaking to college professors, literacy skills are abysmal. The experts never considered the fact that it’s not just reading. Writing and spelling are also essential elements of literacy. I call it the real “eternal golden braid.”

Students need a lot of things that involve gaining knowledge and skills but which may not be necessary when it comes to making a living. When will students use history or science? And yet, learning history and science have always been thought crucial to help us as people make sense of our world and be considered educated. More than our world, these days we have to make sense of our Universe. We need as many avenues as possible to understand the ten thousand things and to make sensible decisions.

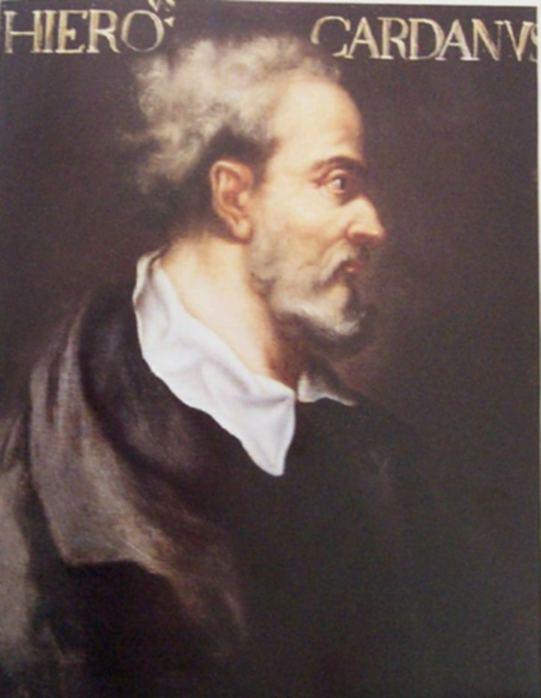

Italian mathematician Girolamo Cardano published the solutions to the cubic and quartic equations in his 1545 book Ars magna.

A popular educational buzzword (buzz phrase?) is “critical thinking skills.” Don’t worry about memorizing facts. Just go right to those critical thinking skills. Teach those kids to think.

OK. How?

If students don’t have the facts, how can they think critically? For example, Let’s say you are one of those students for whom facts aren’t important. You are in a coffee shop. You’ve made up your mind that you want a pound of Ethiopian Harrar. Oh wait. Did I mention that you’re visiting a foreign country? Oops! Sorry. Forgot. The coffee shop is in a country that uses the metric system, and you don’t know how to convert pounds to – uh – what is their unit for weight again? You are missing the information you need to engage your critical thinking skills. The people behind you, who feel they’ve already waited long enough for you make up your mind, are in no mood to wait even longer while you google metric conversions. They’re already swearing at you under their breath in a foreign language.

Let’s make things easier. You’re buying your coffee locally in Ferndale. The total comes to $17.27. You, because you’re an adult with the necessary skills to make this quick calculation, hand the clerk a twenty and 2 cents because you don’t like accumulating pennies. Will the clerk know how much change to give you or be forced to depend on the computerized cash register to figure it out? Will they look at you in confusion wondering why you – you dummy – pulled out these useless pennies? What facts were not taught to the clerk in order to focus on bogus critical thinking skills? Did the clerk learn algebra, not because algebra is needed to figure out change for a twenty, but because the math skills needed for that transaction are used and practiced, leading toward the ability (we hope) to improvise mathematically, to mentally juggle numbers? There is a lot of talk by educational experts about teaching students to think mathematically. If that were truly a goal, it seems to me algebra would be the way to go.

As long as were on the subject, and if you don’t mind me asking: do you insist your children do their homework and go to summer school while you spend your days playing games on your phone and trading Facebook videos? Does your taste in music go beyond the stuff you danced to and got stoned to as a teen? Does your reading stop at anything longer than an Internet meme? If so, you’re not setting a very good example, are you? Philosopher and longshoremen, Eric Hoffer, back in the mid-1960s, questioned whether we were entering an age when creativity would flourish due to advances in technology and the increase in leisure time. And this was before the Internet, which truly does put the world, past, present, and insane at our fingertips. How do we encourage our children to be part of that creative mass if we don’t set the example and spend more time flexing our brains?

Chinese Algebra | Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art

With all of the resources we have at our disposal, we have no excuses for not continuing our education. Have you seen the courses that MIT has online? Or Harvard? Or Hillsdale? For free? And then there’s Open Culture and their list of free courses, lectures, books, music and other ephemera. And I bet there’s more out there.

In other words – learn, baby, learn.

_____

I’m Harry Onickel. I am a reader. I always have been. I like to think that between reading for all these years, fiction and nonfiction, high and low culture, classics and trash, the acceptable and the dangerous, and just being around for a bit, I’ve learned one or two things and perhaps gained a bit of perspective. In addition to learning, reading makes me wonder. Lately, I’ve been wondering – what lies behind the mask? My blog, occasionally updated, is The Teacher That Exploded.