By Tom Brank

In the year 1701, Antoine Laumet de La Mothe Cadillac assembled some 200 men, outfitted 25 large freight canoes with supplies to begin an arduous and dangerous adventure. Historical records indicate the exhibition was commissioned and financed by Louis XIV, King of France; Comte Ponchartrain, minister of the colonies, and Louis de Buade, Comte de Frontenac, the governor of New France.

Among the men were rugged voyageurs who knew the wilderness well. According to author and historian, Helen Francis Gilbert, divided among the 25 canoes were 100 artisans, farmers and a number of trusted Indians.

A crew of eight was in each canoe including two well-armed uniformed soldiers. Two priests were with the exhibition, one a recollect Father presumed to be Constantin del Halle, the founder of Saint Anne’s (Saint Anne’s is the oldest Catholic Church in the country, after St. Augustine, Fla.) and a Jesuit, Father Francis Valliant de Guerlis.

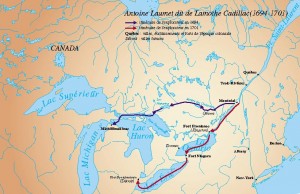

This adventure began its journey just outside Montreal and below the rapids of La Chine on the Ottawa River. It would follow an older and longer fur trade route through Lake Nipissing to the French River and about 30 portages before arriving at the top of the Lake of the Hurons.

The journey of Antoine Laumet de Lamothe Cadillac

Antoine was charged with more than one goal in his contract with King Louis. One was to keep the British out and away from the lucrative fur trade, which the French regarded as their own private enterprise. The other was to block the Iroquois from western expansion, as they were currently at war with the French and engaged in the negotiation of a treaty.

The voyageurs and Algonquin paddled through three great storms after absolute exhausting portages, paddling for 46 days. Once the destination was reached, records say they camped their first night on an island Cadillac called Gross Isle, a place filled with thousands of beautiful songbirds.

On the morning of July 24, in the year of our Lord, 1701, the entourage beached their canoes on a sandy spot with a 50’ cliff. Antoine Cadillac climbed to its top, looked about and said, famously, “Magnifique”, and so d’Etroit was founded.

On that first day, trees were felled for the little log church of Saint Anne’s, along with another temporary shelter for farmers and artisans. Soon after, plans and building began on Fort Ponchartrain. To sustain a group this large, to drink and eat each day, was an enormous task relying solely on hunting and fishing. Drinkable water was not a major problem then, however, even then “wise woodsman” knew to drink from the purest source possible.

Many streams fed the Detroit River. But, one was favored here with Cadillac’s men and local Ottawa; the little Savoyard and its clean source deep in the earth. It bordered the western edge of the fort and could be paddled by canoe almost to its end. Later, its banks were used to picnic and had always set a pretty picture of serenity, a little river that fed the land and nourished its people. A French artisan pulled water from it to make pottery by its banks. His name was Savoy, for which the river is named.

The little river; a prime avenue of life with fish, muskrat beaver, otter and deer drinking at dawn, a river set in a meadow of richness and beauty, a place where even a tough voyageur may come to sit in silence and replenish his soul.

These lands and waters were best described in a letter Comte Ponchartrain wrote to a friend in Paris. “The banks of the river are so many vast meadows where the freshness of these beautiful streams keep the grass always green. These same meadows are fringed with long, broad avenues of fruit trees, which have never felt the careful hand of the watchful gardener; and fruit trees, young and old, droop under the weight and multitude of their fruit and bend their branches toward the fertile soil, which has produced them. Land so fertile and beautiful, it may justly be called earthly paradise of North America.”

Detroit, then, was a place the Ojibway called “bahwating” – a “gathering place.” d’Etroit grew, slowly at first, but it grew. Buildings were made of wood; forts, warehouses and small homes. Then, larger buildings came up and in the 1930’s the little, beautiful Savoyard was channeled into Detroit’s main sewer system, and there it remains today.

In 1925, The Buhl Building was completed, a great building of quality and taste. It sits south of, and next to, the famed Penobscot Building. Oddly, the Buhl is 26 ½ stories high. Technically, to get to the 27th floor one must walk up a Terrazzo tile stairway to the top, where one will find, what was, a semi-private club called the Savoyard.

The Savoyard was used extensively in the heyday of Detroit’s financial district. It has windows facing south to view the river Detroit and was constructed in rough wood, perhaps befitting the little river over which the building stands.

In spite of huge granite and steel, the Savoyard still flows, deep within and beneath the dark recesses of a city. The Savoyard club has been vacant for about 30 years, sitting empty, lifeless and rarely used. Perhaps, it stands as a sentinel, quietly saluting that which has outlived it, the little river that runs beneath.

Tom Brank was born and raised on the Lower East Side of Detroit. He was a broker inside The Penobscot Building in the 1960s and formed Cinema 1976 on W. Grand Boulevard in the early 70s. He now writes from northern Michigan.