Landing was like any other landing into a mid-sized city, brief. I quickly located my taxi driver, who had a sign with my name– my favorite. Just from Lima, I had begun to acquire some routine. Anise tea before coffee and not rising too early– I knew each day I had to carry myself from place to place with cracking camel sandals on my feet, and the knowledge to steer myself from and to suffering. This ‘suffer,’ as I term it, is not derived from the old adage ‘life is suffering’ but rather a state of transportation. It is the pressing need, it is the quest for tiny objects, and the will to breathe. As such, in that moment of sitting in the taxicab, I noted to myself ‘life is not suffering but suffer you shall’ under the sea of life, la vida no es sufrimiento, pero sufrirás.

Skirting along in descent from the plateau of the aeropuerto, through the Cayma district of Arequipa, down one primary road, full of cars– it was I and the driver. My mind could feel all the past moments of myself. The compressed memories of years of sitting in a car, truck, van, train, plane, slow rolling bicycle– looking onward, watching the sloping grasses and emotions surf past my starboard.

It was Saturday night after all, and there are only a couple roads that cut down the landscape to the city centre, thus traffic. My driver was enigmatic in a way that sat well with me, very inquisitive, but without propositions. We both were so-so with either language, so opted for an onboard Google translator. His name was Julius or Julio, something like that. He was average height and build, short black hair, a puffy black jacket, double blue mask. I got the sense he and I were keen on the ‘suffer but not suffering’ portrayal I ascribed above. We talked of our professions, local politics, travel dreams— much more refreshing than the muy masculine chats I have had with other taxi drivers, which usually are about female body parts, money, American imperialism, or just downright muscle milk verbiage. As we passed a bridge with protestors gathering above, he ascertained my political preference of genuine experience and assertion– to then breach his own anger with the protestors. Apparently, they were the so-called opposition that viewed the current President of Peru, Pedro Castillo AKA El Profe, as a ‘communista’ because of his apparent socialist leaning. Or maybe as Julio had extrapolated because El Profe was a schoolteacher and union leader before being elected, and thus was a communist. On this, I didn’t press further. Though, as a footnote, here are some reported hot tips on El Profe.

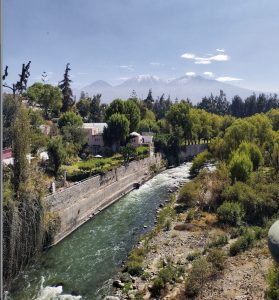

- Arequipa from a Bridge

- A Side Street

- Plaza de Armaz

Unlike Lima, it was quite dark around 18:00 and all I could see were the lights of the short buildings in the distance, rear ends of cars, the hardened embankment and small shrubs that comprised the edge of the road. Occasionally someone would walk by, or be sitting on a stony ledge, sifting through some cloth bags or peering at their phones. I was feeling that spark of travel again, something new to explore, and for a time, risk. Unlike my judge-then-let-go motions in Lima, the spark was back.

I bought some water, before checking into my hotel, then bedded down. On the advice of my friend Patty, I had prearranged for medical evacuation insurance, if shit were ever to hit the fan and I had to leave the country immediately. Covid times are weird. She runs a do-good NGO in Iquitos in the North of Peru, called Amazon Promise. Look it up. Sitting with my insurance, fresh linens, and wifi– I began to plan out where to find the best Baby Alpaca scarves, dusty antiques, sour fruit juices, kindness, and soups.

The next six consecutive days were an assembly of these plans, each set with a daily visit to the main square, Plaza de Armas. On Sunday, many families dressed in blacks, whites, browns, and grays, all walked from the local churches down to the square, congregating and eating ice cream.

Though ice cream wasn’t on my list, an assortment of cafes were. And, similar to some other travels of mine, especially when I was in Armenia, I find that the female attendants in the cafes and lounges I frequent are always so questioning and flirtatious with me. This was the case at my quickly discovered favorite spot in Arequipa, called Istanbul. Go figure. Usually, one of the first questions asked is “do you have a wife back home?” Honestly, my answers vary. Sometimes I leave it to mystery, other times I say yes or no. I get the sense they want to be whisked away, which is a shitty thing to say, I know, but the sense I get nevertheless.

Often complimenting my eyes, ‘bonito,’ ‘guapo,’ etcétera. Other times it is more subtle, asking me first “what do you do for work” or “does your family support you?” In all, each partition of flirt usually concludes with playfulness, then ending rather bittersweet when I leave the city. All the above was the case at my spot, Istanbul. It’s an experience that repeats itself. Similar to the motions of memory in the taxicab. Life is cyclical.

- el buda profano

- (no words)

What wasn’t cyclical was the best vegan sushi of my life. No words. Light, savory, sour, sweet, a tinge of salt, sustainable– everything. el buda profano, with their shiitakes, tomato petals, cashews, and algae had me returning each day for lunch. In all honesty, they defined what food should be about, and I would literally food-travel thousands of miles again just for another bite.

Aside from vegan sushi, in a place that enjoyed pork and guinea pig meat, one of the best things in Arequipa, as an outsider, was the garbage truck ensemble blasting Under the Sea, AKA Bajo el Mar. Knowingly it is a different experience to the locals, likely annoying. I actually asked a new friend I made in Lima about those garbage trucks, days later. His eyes perking then, he said ‘yes, seeing a space with fresh eyes, as an outsider. I can appreciate that.’ A point of reference that continued my spark.

Back in Arequipa, I thought the garbage truck ensemble was the most joyful yet mundane episode of the everyday. They played such a bright version of the song without vocals. Wearing the signature maintenance uniforms with duffel-like hats, seen in Arequipa, of a thick-clothed reddish brown. And, dashing side to side grabbing trash between musical notes, the song looped continuously. I was taken.

But that first time I heard the music hit the street, in a flurry, attendees and workers in all the businesses and stalls stood, stopped, grabbed, scooted, and ran toward the truck– as if missing it meant an unforgivable wait until the next one. The movement in unison concerned me at first, arranging my things quickly in the moment, in case I needed to join the dash. Volcano Misti lay in question in the distance, and I had only recently placed the entrails of How The Earth Was Made mini-series from my mind— a geology TV show on Amazon Prime that scientifically proves, via rocks, that we are all going to die. This mental jog between mad rush and volcanoes, in the moment, was a lapse in social reality. Though, it was welcomed.

In simplicity, among the motions of food, hot midday sun, and colonial iron gates, it was just me and the marimba sounds of the garbage truck, zigzagging along the way.